His personality has often been described using the stock phrase genio + sregolatezza (genius and dissipation): Manzoni did love to have fun and stay out late ; he loved women, booze and everything most twenty-somethings love to do. But he loved even more to travel and determinedly present his artistic work : “Anyway, what counts is to make my talents – and I know I have some – bear fruit in order to make my life the best and most useful thing it can be.” Raised in an environment that was bourgeois, aristocratic and Catholic, but not bigoted, Manzoni believed more in individual ethics than in anything else. Which is why the studio was the most important place to him : the setting in which he developed his art by himself, out of ideas and not received opinions. And it was in his last studio, at via Fiori Chiari 16, that he died in early 1963.

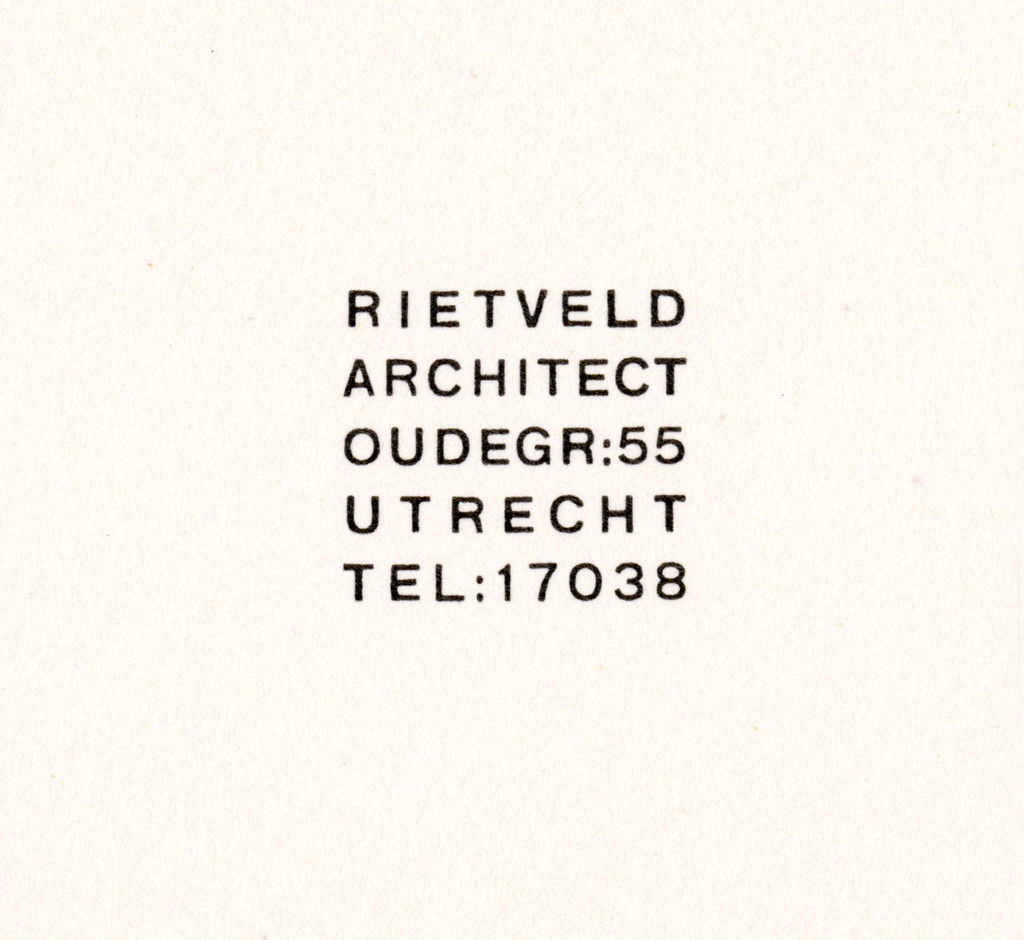

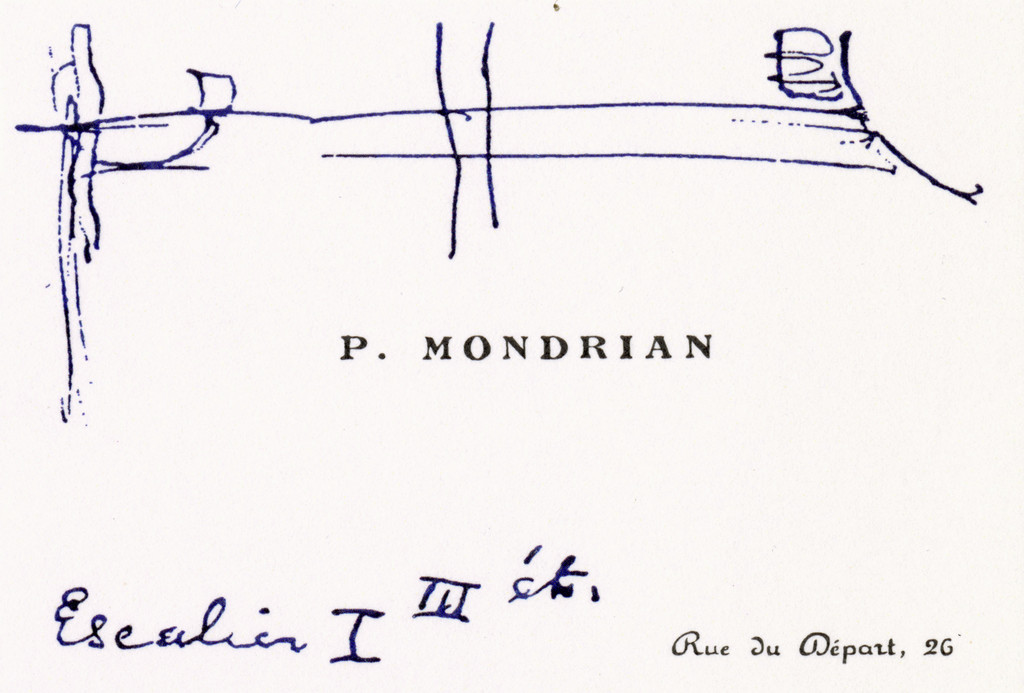

His whole life in Milan revolved around the Brera district, which is home to the Academy of Fine Arts. While his home address remained the same at via Cernaia 4 – the telephone number there (Ab. 66 29 29) appears at the bottom of his business card, under the phone number at his “NEW ATELIER”, he successively used three different studios in the vicinity.

The first was on via Montebello, where he worked from the second half of the 1950s after having quit studying law in Milan and philosophy in Rome. He knew he wanted to devote himself to painting, but writing was still an option at the time. He wrote continually during those years, chiefly in connection with his involvement in the Nuclear Art movement (see the group’s manifesto Contro lo stile [Against Style]).

Between 1958 and 1959 he moved to another studio on via Fiori Oscuri, where he wrote less and painted more – because he felt art should speak for itself. He worked on white surfaces coated with gesso (gypsum or plaster of Paris and glue) or soaked in kaolin (specialist clay), which he called Superfici Acrome (Colorless surfaces). He made the most of some shops near the studio, including the Crespi paint shop and Sciardelli stationery on via Palermo, but above all the printer’s shop of Antonio Maschera, whose typography was crucial to the development of Manzoni’s works on paper with calendars and letters of the alphabet.

It was also in this second studio that the idea of Linee (Lines) took shape, Manzoni’s “most exceptional discovery”, according to his friend – and putative father – Lucio Fontana : each Linea comprised a black line drawn the length of a long strip of paper, which was then rolled up and placed in a labeled and signed cylindrical cardboard tube. A few months later, Manzoni teamed up with Enrico Castellani for a two-pronged experiment, launching a magazine called Azimuth and a gallery with almost the same name, Galleria Azimut. The second issue of Azimuth, printed in January 1960 in Italian, French and English, featured “Libera Dimensione”, an article in which Manzoni declared he was “quite unable to understand those painters who, whilst declaring an active interest in modern problems, still continue even today to confront a painting as if it was a surface to be filled with color and forms which can be more or less appreciated, more or less guessed at. […] Why shouldn’t this surface be freed ? Why not seek to discover the unlimited meaning of total space, of pure and absolute light ? […] The issue, for me, is to give an integrally white (or rather, completely colorless, neutral) surface that goes beyond any pictorial phenomenon, any intervention that is foreign to the surface’s value : a white that is not a polar landscape, an evocative matter or a beautiful matter, a sensation or a symbol, or any other thing ; a white surface that is a white surface and that’s it […]: being (and total being is pure becoming).”

He went on to focus on the allusiveness and disappearance of works of art. Increasingly bent on making his mark throughout Europe, he wrote to friends that he was spending everything he had on travel and had produced what he would subsequently call Corpo d’Aria (Body of Air) : “a pneumatic sculpture : you blow it up with a pump, then deflate it and take it away : extremely handy for shows abroad !”

In those years his work came to be understood and appreciated in Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany and, above all, Denmark, where in June and July of 1960 he first exhibited his Consumazione dell’arte dinamica del pubblico divorare l’arte (Consumption of Art by the Art-Devouring Public) : on a small table he placed some hard-boiled eggs, each bearing the artist’s thumbprint, which could be eaten on the spot for the price of roughly two thousand lire (Copenhagen, Køpke Gallery). He also produced his longest Linea, 7.2 km, in Herning, Denmark, hoping someday to connect up all his Linee into a line as long as the earth’s circumference.

Buying a work by Manzoni means buying Manzoni, his breath in Fiato d’Artista (Artist’s Breath) to fill his bodies of air in Corpi d’Aria (Bodies of Air), and his excrement in Merda d’Artista (Artist’s Shit). Each can was labeled in Italian, English, French and German : Artist’s Shit, contents 30 g net, freshly preserved, produced and tinned in May 1961 and signed by the artist in capital letters. His Sculture viventi were also signed in all caps : with a resolute and yet amused look on his face, the artist would write “MANZONI ’61” on the side of a female nude, his “Living Sculpture”. He went from hired models to perfect strangers, even fellow artists and friends like Marcel Broodthaers, whom he had met in Brussels, and Umberto Eco (Manzoni’s last signing, in June 1962). All that was then needed was the artist’s certificate of authenticity and a pedestal to turn a human being (Base Magica) or the whole world (Socle du Monde or Base of the World, a large metal plinth similar to Base Magica but turned on its head), as if by magic, into a work of art.

“We can’t leave the ground by running and jumping, we need wings : alterations are not enough, the transformation must be all-embracing,” wrote Piero Manzoni. Now that the artificer, idea and artefact at long last formed a unique and indivisible entity, Manzoni felt his oeuvre had become recognizable and the time had come to compile a systematic catalog of his works.

But he did not get around to it in time. He died of a heart attack on February 6, 1963, age twenty-nine, on the ground floor of his “NUOVO STUDIO NOUVEAU [sic] ATELIER NEW ATELIER”. His life and art were cut short. The obituaries announced the death of a young avant-garde painter.

![The Futurist Group (Jannelli, Depero, Prampolini, Azari, Bisi, Marinetti, Lescovic, Casavola, Pinna, Somenzi, Russolo, Vianello – to the right of Russolo – Paoca, Mazza), undated [c. 1912]. Photographer unknown, image layout design by Fortunato Depero. Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library (Filippo Tommaso Marinetti papers), Yale University, New Haven, CT. - © Oracles: Artists’ Calling Cards](https://oracles.editionpatrickfrey.com/media/pages/chapters/deal-ten/eva-fabbris/5f92cbbd28-1565630200/marinetti-400x.png)