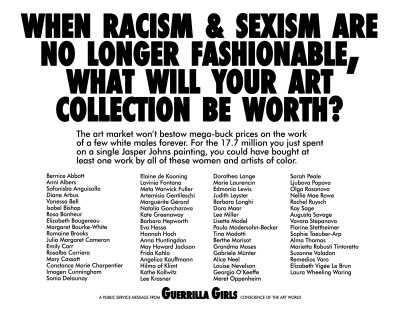

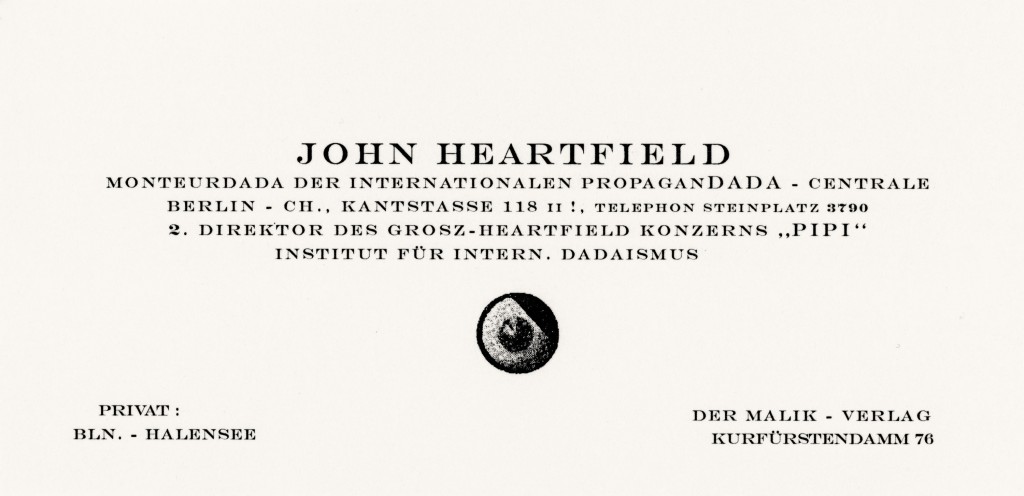

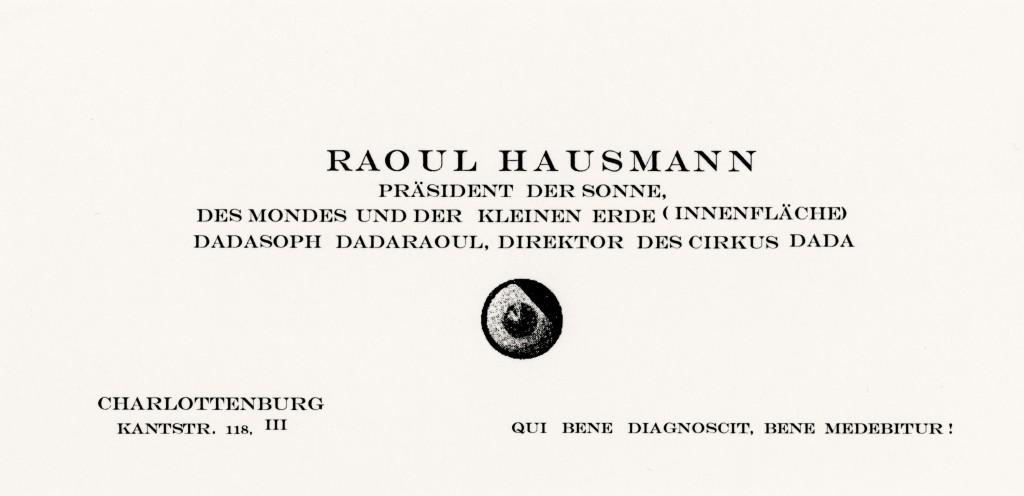

This surprising impression of functionalism fades away upon perusing the few lines of outrageous sobriquets and contemplating the sort of stylized eye floating underneath. The top right segment of that “eye” sports a diagonal hatching that recalls an infamous strand of hair whose possessor was, that year, none other than the charismatic propagandist of the newly-formed Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, not yet the hysterical tyrant against whom Heartfield would soon produce dozens of scathing photomontages. The real origin and properties of this pictogram remained a riddle for the time being. Leaving aside the enigmatic eye and the epithets, the sheer contrast between the object itself, that is the business card, with its load of social conventions, and the radical Dadaist undertaking was already doubtless a strategic choice.

In 1917, rallying around the aforesaid Huelsenbeck, a renegade from the original core of the Dada movement in Zurich, the members of the Berlin Club delighted in subverting conspicuous signs of respectability. Their monocles, solemn incantations and extravagant titles were part and parcel of this crusade against all things grandiose, against the pride of the artistic elite, against the bourgeoisie, against civilization, against the “cacacosmos organisé”, as Hausmann called it retrospectively. Their aim was to disrupt. Disturb. Disconcert. Disorient. Discompose. Debunk. And then finally perhaps, as Tzara put it, “balayer, nettoyer” (sweeping, cleaning) (Tristan, Tzara, “Manifeste Dada 1918”, Dada3, Zurich, 1918) – to make a clean sweep. But this Club Dada, as fervently Dada as it may have been, was still a club, whose doors remained closed to the likes of Kurt Schwitters, who once tried to gain admission through the good offices of Raoul Hausmann. Behind all the virulence and the scandals, their sophisticated posturing and business cards, as caustic as they may have been, reflected a penchant for a certain dandyism, a refinement that could not be reduced to pure satire.

This was not one of the least paradoxes of a movement celebrating “the contradictory nature of man” (Hausmann) and based on the injunction that to be a Dadaist means first of all to flout the fundamental principles of Dadaism : the cream of the bohemian avant-garde espousing the Spartacist cause ; anti-establishment artists attacking art, its independence and grandeur, who were to spend much of their lives assailing one another’s claims to discoveries and inventions (choosing names, the invention of photomontage, the authorship of the manifestos etc.). These conflicts would continue to afflict John Heartfield when he decided to devote his most creative energies to the great proletarian cultural revolution : the German Communist party likened his militant photomontages to “bohemian bourgeois decadence” that would only sow confusion among the masses in search of a political orientation. The Berlin Dadaists, a motley crew pursuing a mixed bag of objectives, wanted above all to be the mirror of a German society traumatized by the war and grappling with the symptoms of a nervous breakdown. John Heartfield, along with his brother, Wieland Herzfeld, and the painter George Grosz, embodied the group’s most radical fringe. Georg Gross and Helmut Herzfeld had already changed their names to Grosz and Heartfield in 1916 in reaction to the unbridled nationalism sweeping across Germany. On December 31, 1918, Heartfield, Herzfeld, Grosz and stage director Erwin Piscator joined the Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands, which had been founded only the day before by Rosa Luxembourg and Karl Liebknecht. The Austrian Raoul Hausmann, for his part, too individualistic for Bolshevism and perhaps ultimately more attached to his liberties than to the class struggle, refused to resolve Berlin Dadaism’s essential tension between political and artistic idealism. He felt that politicizing Dada was a mistake, that Dada should, on the contrary, enable art to divest itself of any trace of utility. Together, Heartfield, Hausmann and Grosz organized the First International Dada Fair in the summer of 1920, bringing together 174 works by 27 artists, an exhibition that would mark their last collaboration and the dissolution of the Club Dada, undermined, as it was, by internecine strife and the public’s widespread fatigue.

![Émile Gallé,* Cocotte Porte Saint-Georges*, ceramic origami fortune-teller to hold visiting cards, with a monochrome design (inscription:* Démolissons-la* [let’s demolish it]), 1883–1884. Photograph by Michel Bourguet. Collection and courtesy of Musée de l’École de Nancy. - © Oracles: Artists’ Calling Cards](https://oracles.editionpatrickfrey.com/media/pages/chapters/deal-sixteen/charlotte-magnin/bc2aa9ad5e-1565640516/m0513-2006-2-1-applat-400x.png)