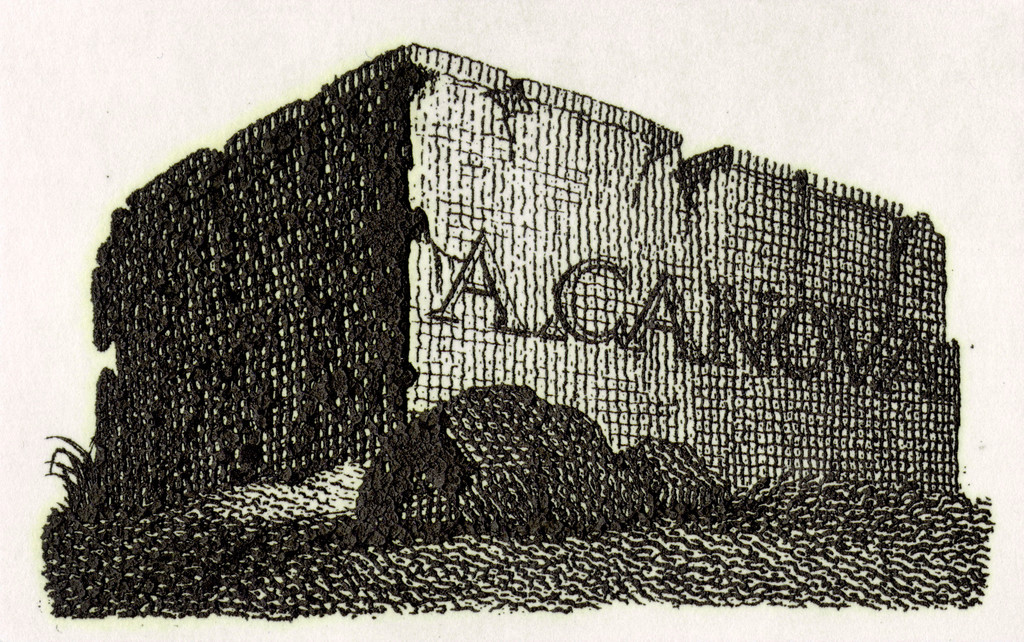

Fuori dall’Arena (Out of the Arena) is the title attributed to this Pietro Fontana etching. Fontana, a contemporary of Canova and fellow Italian, was his favorite engraver. And he is undoubtedly its veritable creator, since unlike most of Fontana’s clients, he was no stranger to brush or chisel. But the question remains : what arena or battleground is here portrayed ? That of the human condition, abandoned at last in favor of heavenly delights – just desserts for a life spent in large part in the service of the omnipresent Catholic Church, not to mention that his half-brother Giovanni Francesco Sartori was the Bishop of Mindo ? Or the war that he was obliged to wage in order to impose and perpetuate his artistic conceptions – no easy task seeing as a new wave of young artists was already busy rejecting them ? Or simply the political, military, aristocratic, ecclesiastical and social elite into which, very early on and with stupefying ease this son of a stonecutter inserted himself, experiencing nary a glitch in a career spanning nearly fifty years ? Or a European continent shaken to its core by the political and social upheavals brought about by the French Revolution ? Or, to quote Starobinski : “That desire for eternity through form [that] arrives at a moment when History has its foot on the gas pedal” ?

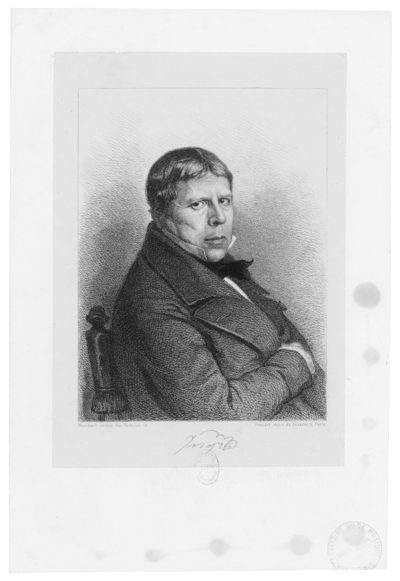

Canova settled in Rome in 1780, and became a member of the Academy of San Luca in 1800. He led a solitary existence given over to fanatical work habits. His efforts were crowned by numerous honors, and soon he was rich. This prosperity made of Canova a businessman-artist, a kind of precursor to contemporary art stars – somewhere between Frank Gehry, Daniel Buren and Jeff Koons. Though he refused in his lifetime to designate a disciple among his students, he would never have been able to bring to fruition such a vast and prolific body of work without his team of assistants, whose every move he choreographed like a ballet master. He was not the only artist to go this route, and subsequently figures such as Frederick Winslow Taylor and Henry Ford proceeded in much the same fashion. All of this took place in Canova’s studio on via San Giacomo, in Rome. He systematically had multiple copies of his works made, each time (partially) reinvented, ensuring that his work reached audiences far beyond Italy : in France, England, Austria, Tsarist Russia and the New World. A great admirer of Bernini, Canova through sheer hard work became one of the pillars of Neoclassicism ; his Theseus and the Minotaur, produced between 1781 and 1783, is its manifesto of sorts.

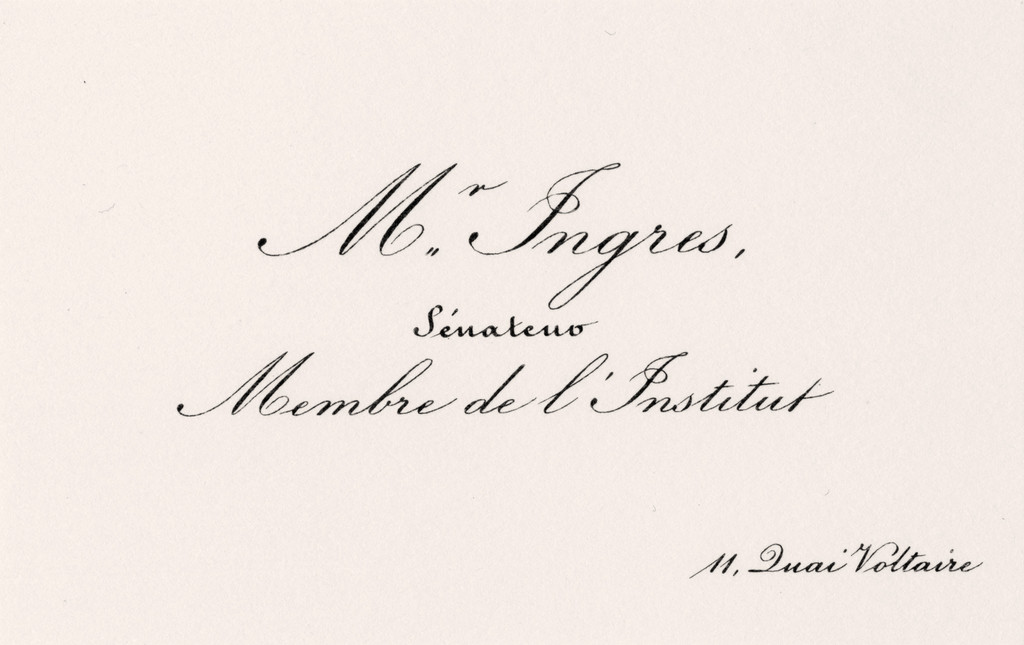

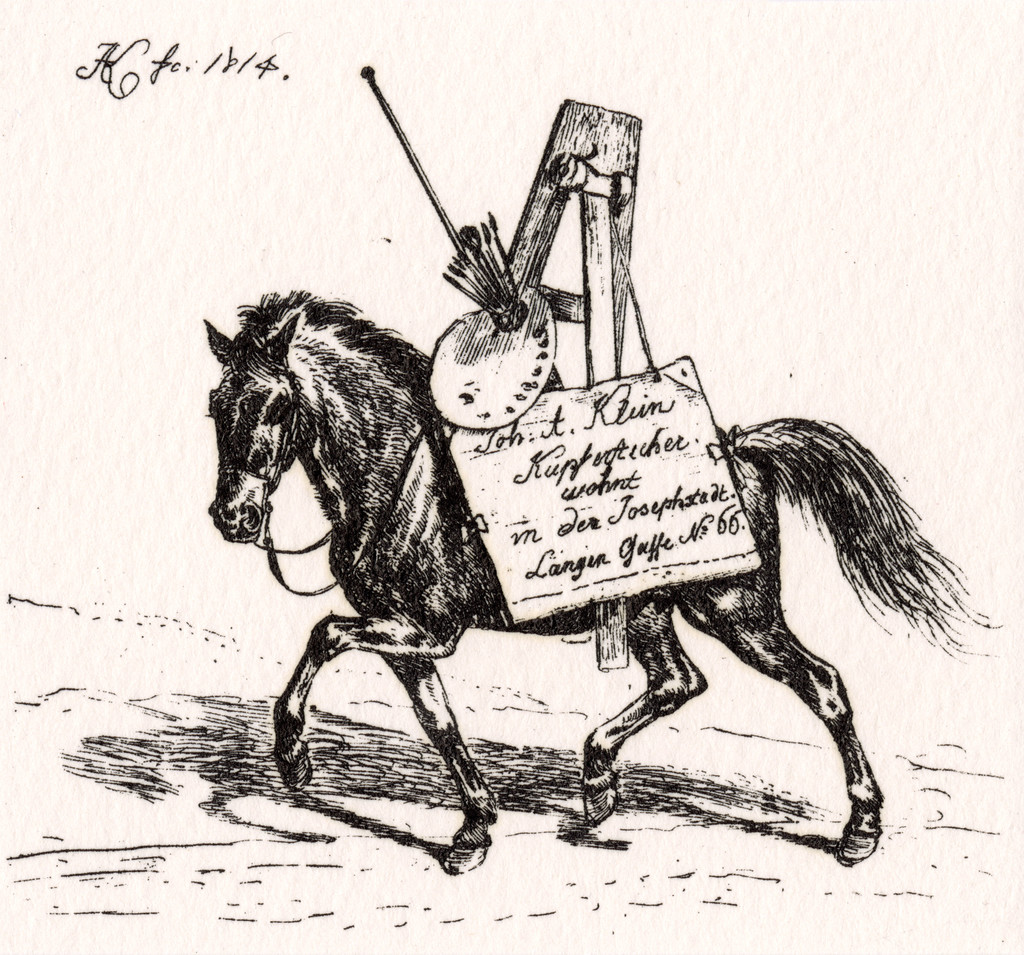

But what does the block of marble engraved on that card – apparently about to explode, its surface carefully bush-hammered, adorned with an understated upper molding – actually represent ? The cracks the artist has outlined prevent the viewer from ascertaining if the tomb has been excavated : if it has not, we are perhaps dealing with the base of a statue of Canova himself, or one of his works – Hercules and Lichas, Polyhymnia, or Sleeping Nymph come to mind ; if it has, we might be dealing with the tomb itself serving as the base of the statue of the deceased, such as he had sculpted for the papal tombs of Clement XIII and Clement XIV, which he worked on concurrently in 1783 : two works considered at that time to be revolutionary because of the unheimlich emptiness they produce in their very core. However, absent statue – destroyed ? lost ? – or solitary tomb of the artist, this block of marble implicitly projects its protagonist into an elsewhere that turns his present into an already faraway past, transmuted by the alchemy of time toward a new Antiquity. The holder of this visiting card infused with the black light that Victor Hugo is said to have seen on his deathbed, was himself neither living nor dead ; he was floating in a kind of purgatory that could signify eternal oblivion or everlasting glory. In both cases, the tomb is empty.

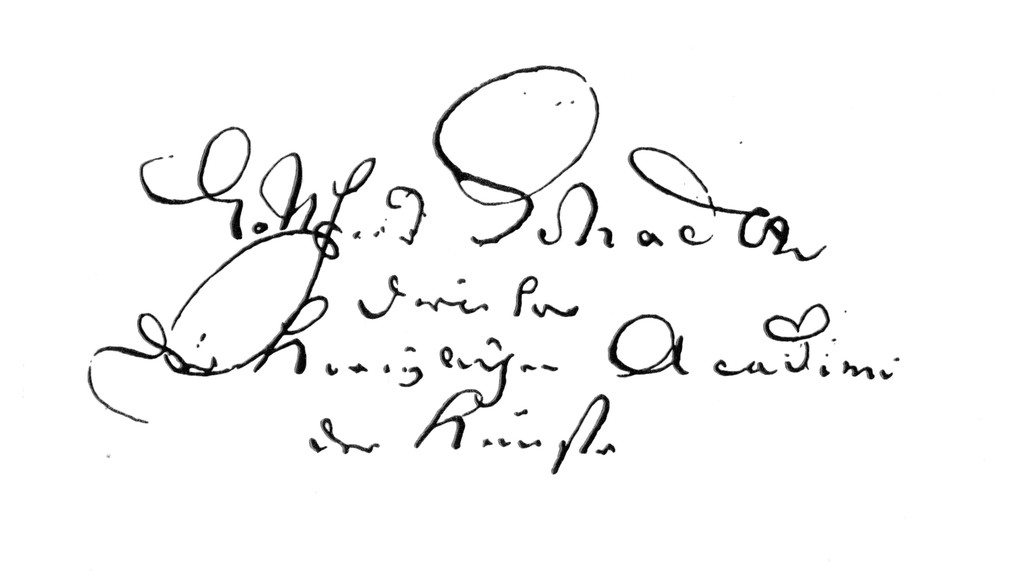

Eternity is also the motor behind another card linked to Canova, giving access to the numerous happy few who were lucky enough to be invited to the Rome funeral of the celeberrimo scultore. Canova died in Venice on October 13, 1822 ; his funeral was held three days later – the time necessary for a resurrection – in St. Mark’s Basilica, but the Romans took more than three months to put together the spectacular stagecraft that for one day, on January 31, 1823, transformed The Church of the Twelve Holy Apostles into an ephemeral museum to the glory of Rome’s adopted son. This card bears the heraldic badge of the San Luca Academy – with its slogan “AEQUA POTESTAS” taken from a line of Horace, alongside the symbols of the artist’s multi-faceted talents : chisel, brush and compass – yet it is articulated around an ouroboros, the image of a serpent devouring its own tail, symbol of eternal return.

In truth, if Canova was able to ensure the immortality of his name and work, it is thanks in part to the pragmatism and efficiency with which in 1815 he negotiated the return of works plundered by Napoleonic troops, an achievement pursued in concert with one of his few close friends, Antoine-Chrysostome Quatremère de Quincy – and which led Pius VII to ennoble him with the enviable title of Marquis of Ischia. However, it was at Possagno, his native village, lying in the shadow of the Monte Tomba, that the artist built the two towers that would forever guarantee posthumous fame : the high blind facade of the cast gallery, which looks like a burial site, and whose layout presents close architectural affinities with one of the most famous and most modern antiquities museums of its time, the Vatican’s Museo Chiaramonti, created by Canova for Pius VII in 1807 ; the Tempio Canoviano, monumental Neoclassical church based on Rome’s Pantheon for the volumes, and the Athens Parthenon for its architectural order, the cornerstone of which he set on July 11, 1819. It was a structure for which he was at once the architect, sponsor, and rightful addressee – with due reverence to the Holy Trinity, to which it is officially dedicated. His mortal remains are there now, along with those of his half-brother, in an urn worthy of his immoderation, inspired by the one he had himself designed for Horatio Nelson ; as for his heart, it is still in the pyramid tomb he had planned for Titian, in the Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, in Venice. Built by his students on the profoundly singular model (for the first time in history, figures deliberately turned their backs on the spectator) of the one he had devised for the archduchess Maria Christina, Duchess of Teschen (who died in 1798) in the Augustinian Church of the Hofburg Palace in Vienna.

— His epitaph ?

— HIC CANOVA.