She spoke in voices that were not her own.

Failure, excess and debauchery were the principles of a world all his own.

He purportedly consulted his tarot cards and then agreed.

She spoke in voices that were not her own.

Failure, excess and debauchery were the principles of a world all his own.

He purportedly consulted his tarot cards and then agreed.

Carla Demierre — Transmitting messages and communicating with those absent, tuning into a realm of invisible information, electrifying cities to illuminate their interior lives : such were the obsessions of the 19 th century, which discovered or invented the telephone, radio and telegraph as well as the unconscious and spiritualism. The women of the age were mental radios, receiving spectral and subliminal signals through portals called “nerves”. The Fox sisters, Eva C., Leonora Piper, Eusapia Palladino, Hélène Smith, Anna O., Blanche and Dora, heard voices and knocking, and delivered messages from beyond. They were wild-eyed clairvoyants, ventriloquists for ghosts, masters of illusion, whilst occasionally suffering from “melancholic delusions” in their everyday lives. Others would watch, mesmerized, as the medium arched her body like an arc of electric current and entered into a special sort of sleep. Hypnosis, sleepwalking, catalepsy, trance are astounding – and photogenic – states of consciousness. The rigid cataleptic is submerged in the state of a living photograph. The camera merely serves to give material form to what the eye desires to see. These states of consciousness can be easily triggered with a tuning fork, smoke and mirrors, a scent, an electrical impulse, pressure applied to a pressure point.

Hélène Smith prefers to hypnotize herself. It is not till the fourth seance held by the medium, in January 1895, that psychologist Théodore Flournoy tries to touch her hand, or rather prick it with a pin to elicit a reaction, only to find she feels absolutely nothing. Hélène is thirty-four when she meets Flournoy. Two years before that she discovered spiritualism through a friend, Madame Y., who took her to Madame Z. for some automatic writing experiments with “eleven people seated around a large, heavy oaken dining room table.” At the third seance Hélène sees an illuminated ball. Next time around, long ribbons. Certain visions form unexpected loops in her conscious memory. The hallucinated vision of a straw hat stays with her for days after Flournoy fans her with his hat. When she snaps out of it, she asks, “What time is it ?” The psychologist is there for most of Hélène’s trances from 1894 to 1899. She takes notes on any automatisms she experiences outside the seances and they discuss them. She is a rather tall beautiful brunette with a deep gaze.

Her parents were “neither nervous nor psychopaths”. Her father was Hungarian. Her mother practiced “table-tipping”, a type of seance much in vogue in Europe at the time. We don’t know much about her childhood. She grew up in Geneva. She was said to be fearful : “At night she shudders at the slightest noise, the sound of furniture crackling.” In her normal state, Hélène Smith was perceptive and slightly eccentric. Her everyday automatisms were sufficiently superficial and transitory as to go unnoticed. What remained was a memory saturated with details and an uncanny ability to find lost items. She had always loved needlework : “when your hands are occupied with mechanical movements and your thoughts can roam freely.” Flournoy considered these reveries the “prelude to her major somnambulatory novels” to come. She was employed in a big draper’s shop. We know nothing about her love life. In her parents’ house she had a small sitting room decorated to her taste, with prints on the walls, plants, flowers, “curiously framed” photographs, a self-made lampshade and embroidered rugs. There was “something original, bizarre and graceful” about the overall effect.

Élise Müller, La Fille de Jaïrus (The Daughter of Jaïrus),

3 August–15 September 1913, oil on canvas, 51.6 × 42 × 1.9 cm.

Collection LaM, Lille Métropole, Musée d’Art moderne, d’Art contemporain et d’Art brut ; Villeneuve d’Ascq. Photograph copyright Philip Bernard, courtesy of LaM.

Just a few weeks after her introduction into spiritualist circles, Hélène Smith began eliciting responses from the table, receiving messages through automatic writing, hearing voices, progressing from her first, rudimentary hallucinations to complex visions that would become the subject of her unusual novels. She became renowned for the diversity of her automatisms. Her seances, conducted free of charge, were of an unprecedented richness. She spoke in voices that were not her own. Her writing was distorted according to her various incarnations. Unknown characters showed up in her regular writing. Occasionally she spoke in singsong rhymes, as in Vous détestez les omelettes. Autant que moi les côtelettes. (You hate omelets. Just as I hate cutlets.) – when she wasn’t speaking in strange or disguised tongues (Martian, ultra-Martian, Uranian, Sanskritoid) –, and often lent the fingers of her left hand to a spirit named Leopold so he could enlighten the living on any number of different subjects. All of Smith’s automatisms communicated to produce subliminal fictions that Flournoy called the Royal Cycle, the Hindoo Cycle and the Martian Cycle. Three “novels that intersect and spread out in time, interweaving from one trance to another the lives of a Hindu princess (Simandini), a queen of France (Marie-Antoinette) and a community of Martians.

Flournoy presented an extensive study of the medium in his book Des Indes à la planète Mars (From India to the Planet Mars), which came out in 1900, followed two years later by Nouvelles observations sur un cas de somnambulisme avec glossolalie (New observations on a case of somnambulism with glossolalia). It was this French psychologist who turned Élise-Catherine Müller into Hélène Smith, a creative medium who captivated psychoanalysts and linguists as well as artists and poets with the complex, naive beauty of her inventions and her gift for crossing back and forth across the threshold of consciousness. Lacan nicknamed her “the delirious clairvoyant with the marvelous name”. For André Breton, she was a “human document” with perfect automatisms. The Surrealists devoted a card to her in their Tarot de Marseille deck. Her glossolalia also intrigued literary and sound poets, with the advent of the tape recorder and a taste for distortions of the human voice. Raymond Hains, who was interested in the language of birds, had a copy of Des Indes à la planète Mars, which he would re-read when he wasn’t busy playing records backwards, listening to Pygmy songs or Tuareg lullabies for the “pleasure of hearing a language spoken without trying to understand the meaning”. Hélène Smith was a fabulous example for those seeking “the breeze of the illegible, the unintelligible, the open-ended”.

We know little about Smith’s life during the thirty years following the publication of Flournoy’s book. She moved away from spiritualist circles, distanced herself from the scientific community and began painting religious visions on large wooden panels. She photographed every stage of their execution and recorded the details of her visions in her diary. But these sixteen paintings as well as the photographs and written documents subsequently vanished in mysterious circumstances. Élise-Catherine Müller died on June 10, 1929, in her small apartment on rue Liotard in Geneva. She had probably never set foot in the United States or actually used the name Daggy, the meaning of which, however, does indeed characterize the medium and her life : disheveled, eccentric, bizarre.

Marvin Heiferman, Carole Kismaric, Edward Leffingwell (eds.) Flaming Creature. Jack Smith. His Amazing Life and Times, New York, Institute for Contemporary Art, P.S.1 ; Pittsburgh, Andy Warhol Museum ; Berkeley, Berkeley Art Museum ; Berlin, KW ; New York, Serpent’s Tail, 1997

Théodore Flournoy

From India to the Planet Mars: A Study of a Case of Somnambulism with Glossolalia, New York/London, Harper & Brothers, 1900

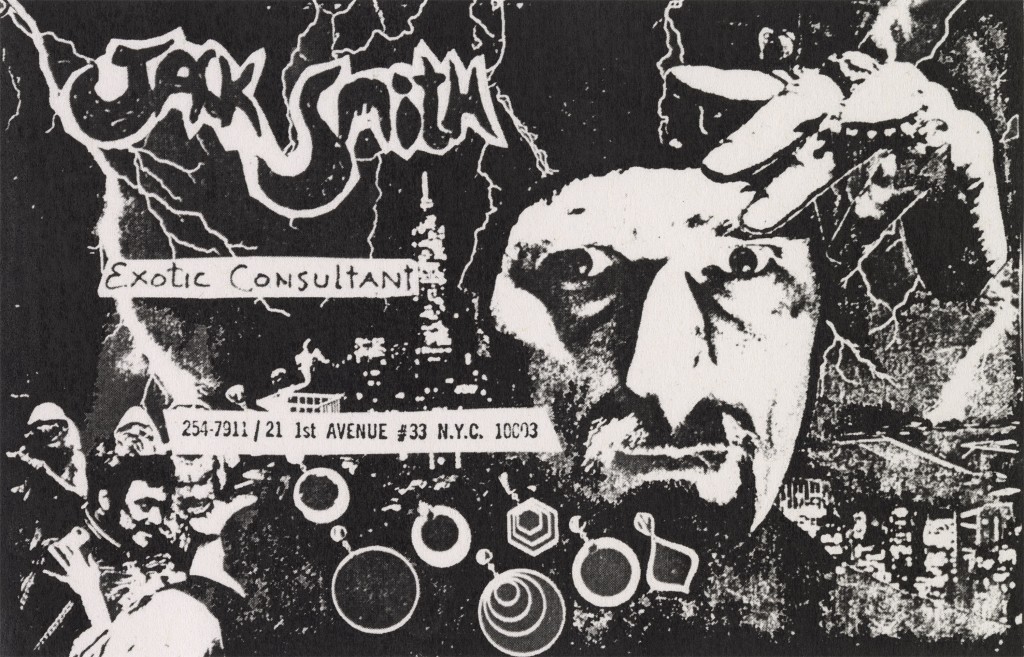

Gesine Tosin — Jack Smith was fascinated by Hollywood films of the 1930s and 1940s, especially the “Middle Eastern” phantasmagorias that whirred on in Technicolor. He was intensely drawn to these exotic worlds (as he was to the mythical continent of Atlantis). The orientalized set designs and costumes, their flamboyant glitz, fed into his own camp Orientalism, a fantasy universe whose lustful excesses would influence his very persona and the imagery of his genderqueer films and performances.

Stimulated by New York subcultures, Jack Smith sought to conceive a counter-world, one through which he could confront the reality that repelled him : US consumer culture and its horrifying excrescences. He aimed his disgust at the bourgeois cultural establishment, its hypocritical art business and the capitalist practice of landlordism. Failure, excess and debauchery were the principles of a world all his own.

To house this alternative world, he created spaces, both real and imagined. Among these were the Hyperbole Photography Studio, which he opened in an East Village storefront space in the late 1950s ; the studio operated more as an ongoing installation and performance space than a commercial enterprise (not unlike Claes Oldenburg’s Store, which opened nearby in 1961). A bit later, he created Cinemaroc, a fantasy film studio with real-life “superstars”. (Warhol embraced Jack Smith’s idea of a bohemian replica of the traditional Hollywood studio, as well as his use of the term “superstar”, and by the mid-1960s many of Jack Smith’s superstars had wandered off to Warhol’s Factory.)

If it had been up to Jack Smith, art would not have taken place in institutionalized spaces. A photograph shows him, together with conceptual artist Henry Flynt, planted in front of MoMA in 1963, a sign around his neck saying “Demolish Art Museums”. His aesthetic celebrates impoverishment and is characterized by the practice of “junking”: on the streets of Lower Manhattan, he gathered whatever could serve as props for his photographs and films (and was not alone in taking this approach either). It was a poetic, alchemical process through which he transformed waste into “art”. His two best-known films, Flaming Creatures and Normal Love, are not his only wildly baroque and “trashy” works ; his slide shows and performances, along with many of his photographs, speak the same language.

In addition to being an icon of the theatrical avant-garde of the 1960s, a central figure of New American Cinema and one of the founders of performance art, Jack Smith was a pioneer in his photographic practice, in which his persona emerged as a kind of obsessive continuum. He was among the first to use color in art photography, although he stopped in 1961 and only returned to color photographs for his slide shows in the following two decades. Until the 1980s, he would invite friends – such as Uzi Parnes and Ela Troyano – to photo shoots and ask them to take pictures of him. He would then use the photos in flyers, posters, press prints and newspaper ads – or, in earlier days, to apply to modeling agencies, hoping to make a living as a model. By collaging some of these portraits into stills from or publicity shots for his favorite movies and re-photographing them, he literally transposed himself into an exotic fictional realm, a “world of delirious unreal adventures” (as he characterized the films of Josef von Sternberg, one of his favorite directors).

Which brings us to “Jack Smith, Exotic Consultant”, a calling card emblazoned with his name, title, phone number and address, all pasted on an untitled photo collage (c. 1978). This time, he is neither a model nor an actor (another whimsical card presents “Sinbad Glick, Oily Actor, I would act in… anything”) – instead, he is Jack Smith the “consultant”. The self-designation was surely tongue-in-cheek (what “clientele” would he have targeted as a “consultant” with this outrageous calling card ?), but it may also have really been an attempt to earn a bit of cash. And it was “exotic”: a photo spread shows Jack Smith in Exotic Motion (1982, photographer unknown), donning a Middle Eastern fantasy costume and a dramatically draped headscarf, much like the one on the calling card. In the photo collage, he is undoubtedly the fixed star of his own fantastical universe, one replete with labyrinthine architecture, populated by surreal Hollywood creatures. But his gaze – direct, stinging and unavoidable – points up another attribute : he presents himself as the one who sees, as Jack Smith the “seer”. The pose of his ringed hand is reminiscent of traditional occult gestures. The skies open up and send down lightning, hoop earrings reveal hallucinogenic qualities. Jack Smith as the medium, the connection to an “unreal” and “delirious” world, the exotic consultant on matters exotically “other”.

Marvin Heiferman, Carole Kismaric, Edward Leffingwell (eds.)

Flaming Creature. Jack Smith.

His Amazing Life and Times,

New York, Institute for Contemporary Art, P.S.1 ; Pittsburgh, Andy Warhol Museum ; Berkeley, Berkeley Art Museum ; Berlin, KW ; New York, Serpent’s Tail, 1997

Dominic Johnson

Glorious Catastrophe. Jack Smith, Performance and Visual Culture, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2012

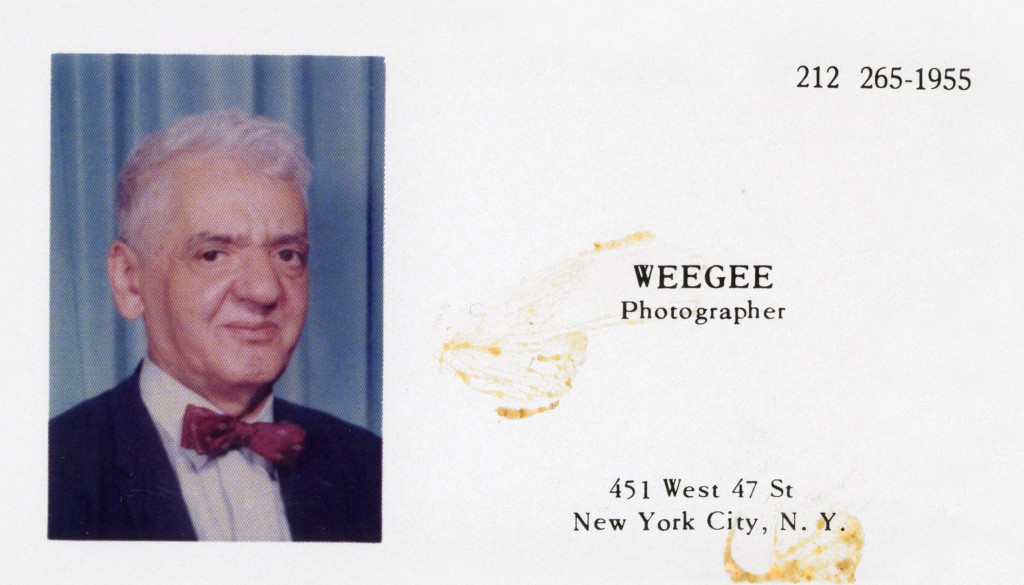

Paul-Louis Roubert — In 1957, Weegee, knowing he was diabetic, moved into a little apartment with social worker Wilma Wilcox at 451 W. 47 th Street in New York, in the heart of Hell’s Kitchen. Although he’d traveled the world from Hollywood to Moscow, Weegee was a man of one sole city, New York, where in the 1930s and 1940s he produced the quintessence of the film noir visual imagery he is most known for. Now on 47 th Street, Weegee, embarking on the second leg of his career, was lodged on the very cross street that led west to the neighborhoods in which Jacob Riis’s flash photographs had exposed the violence of the new mega-city’s slums at the close of the 19 th century, and east to the Silver Factory in which Warhol was to set up his studio in 1964. Like Weegee’s new address, this little printed piece of cardstock dates from the middle of the career of this master of self-promotion through photography.

Born in 1899 in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Usher Fellig came to New York at the age of ten, where he soon became Arthur Fellig and at age fourteen dropped out of school to support his family. Self-taught in everything, Arthur became a photographer after working a wide range of odd jobs including everything from violinist for silent films to darkroom technician for a photographic agency. An early high school dropout, he liked to describe photography as a natural ability in which his talent would increase in parallel to his ability to build his public persona.

He began freelancing for the local press in 1935, specializing in shooting crime and accident scenes dramatized by the nighttime ambiance he loved to explore. Thanks to a radio tuned in to short-wave police frequencies, he would often beat the authorities to the crime scene, like a human ouija : hence the famous nickname Weegee. Actually more of a voyeur than a clairvoyant, Weegee became a New York celebrity on the cusp of the 1940s when he put on his first exhibition, Murder Is My Business. His moniker and motto are associated with the portrait of a man with his eternal cigar sticking out of the corner of his sardonic smile, holding a Graflex Speed Graphic crowned with a flashbulb, the indispensable arm of nocturnal crime hunters in those days and an emblem of postwar tabloid photojournalism. But whereas in 1890 Jacob Riis had terrorized crowds by flash-photographing the new immigrants in Hell’s Kitchen and the Lower East Side like as many criminal suspects, Weegee entered the crime business, fueling the tabloid press by focusing less on potential criminals than on their actual crimes. Weegee’s success attained its apogee when, after his book Naked City came out in 1945, Jules Dassin adapted this New York crime chronicle for the screen in 1948. Weegee’s photographs provided the imagery on which noir films and crime thrillers thrived. His very name became synonymous with the violent images that he turned out in abundance, as if by instinct, and industrially reproduced on a large scale.

And yet already by 1957, the year he had this business card made, he was no longer the same man. While the “brand” endured in lieu of the name – the business card he had used in Los Angeles in the late 1940s had still said “Arthur (Weegee) Fellig” – it was now at odds with the face, no longer that of the famous Weegee. The portrait is in color, taken in a photo booth or a studio. The cigar is gone, as are the Graflex and flash, all three supplanted by the sole attribute of a bow tie. This is not a self-portrait, it is an ID photo for which the subject was clearly prepared. Preserved in the archives of the Andy Warhol Museum, the card probably changed hands when the two men met in 1965, just a few months after Warhol, in the midst of his Death and Disaster series, had seen his mugshots of the Thirteen Most Wanted Men on the facade of the New York State Pavilion censored out, painted over, before the opening of the World’s Fair. When Warhol gave up painting to work on Death in America using mechanical reproductions of violent press photographs, it was only natural the two men should meet. But Weegee had already seen too many dead, and after having permanently yoked his pseudonym to crime photography, he now wanted to be an artist and pursue a playful, experimental sort of photography, the fruit of kaleidoscopic tinkerings, an approach he also used to portray the pre-eminent pop artist himself. Even more than Weegee’s photograph on his card or the card itself, the grease stains on the card attest to the meeting of the two men, maybe over a hamburger, Weegee’s favorite fare, wolfed down at Sammy’s Bowery Follies, right off Great Jones Street. This is where the man who was nothing but a machine met the man who wanted to be a machine. In 1968, Weegee died of a brain tumor and Warhol moved his Factory to Union Square.

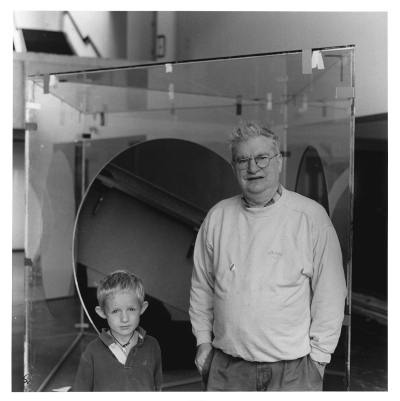

Corinne Diserens — Here is what Dan Graham told me about his business card : “I don’t use the old address, but I use the same image on my current card. It depicts my first realized pavilion for the Argonne National Laboratory in Illinois : Pavilion for Argonne. I don’t have the Knickerbocker Station post box anymore. The post office was in a Chinatown slum.” The card was designed by Louise Lawler, who recalls : “I met Dan at a Blimpie [sandwich shop] in downtown NYC. It is no longer there. Dan was about to go to Japan and was determined to have his cards done before going. I think it was early ’80s.”Graham had a show at Plan B in Tokyo in 1982.

The artist wrote about Pavilion/Sculpture for Argonne in Buildings and Signs (1981): “Because of its double function as architectural pavilion and as sculptural form, a comparison could be made to Rietveld’s sculpture pavilion in the sculpture park of the Kröller-Müller Museum, which is both a sculptural and utilitarian form. Pierced cinderblocks, a high interior window and one completely open side admit air, light and provide unobstructed views of the outdoor works in the surrounding park. There is an ambiguity as to whether the art it displays is in an exhibition space or is outside and still part of “Nature”. A shelter for both the sculpture it displays and for people observing the sculpture, it makes spectators looking at the art within its space a cohesive group and, at the same time, it imposes an order on the works it groups for display. Pavilion/Sculpture for Argonne creates its own social order, one which is based on two sets of social divisions. The first is between two audiences within the pavilion on opposite sides of the diagonal division. The second is between those inside the work and those outside. The pavilion/sculpture will be situated in a wooded area at the front and to one side of a new Administration Building designed by Helmut Jahn. This building makes use of a solar energy-efficient design, which also symbolizes the sun as energy source. It is a semi-circular, glass-sheathed form, flat in the front, with the rest of the implied circle completed by a reflecting pond. Angled frames on the front facade are designed to accommodate solar collectors, should this become economically feasible ; they would also prismatically reflect the sun. In this setting Pavilion/Sculpture for Argonne is analogous to a small, rustic or Rococo pavilion in relation to the larger building’s technological “Versailles” symbolism. The sculpture/pavilion is aligned to the point where the building’s front facade ends and its left side begins to curve. It is also aligned with the curve of the access road on its other side. It can be seen either from a car (where it is larger in scale than the Administration Building behind it) or approached on foot. Its orientation is such that the two interior mirrors catch the sun’s reflection during the morning, creating a prismatic reflection in relation to the angled, sun-reflecting elements of the building. The diagonal element of Pavilion/Sculpture for Argonne, if extended toward the building, would perpendicularly bisect the diagonal floor plan of the building.”

Installation of Dan Graham’s retrospective, Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art, Helsinki, 2002. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the artist, New York, and Corinne Diserens, Berlin.

When I asked Graham about the architects’ astrological portraits he wrote with Jessica Russell for Domus, he replied : “My early and some later work deals with magazine pages and popular cliches. Horoscope columns and magazines are very popular and deal with readable cliched ideas. Art‑making for me is a passionate hobby ; architecture tourism and writing spontaneous “off-the-cuff” texts on architects and architectural ideas/experiences has been a pleasurable hobby for me as well.”

Dan Graham

Two-Way Mirror Power. Selected Writings by Dan Graham on His Art, Cambridge, MA, The MIT Press, 1999

Dan Graham and Jessica Russell — Le Corbusier : Diplomat, Mediator, Indecisive, Easily swayed, Romantic, Charming, Flirtatious, Easygoing, Sociable, Peace-loving, Self-indulgent, Gullible. As a Libra, symbol of the scales, Le Corbusier’s love of balance can be seen in two of his seminal drawings. One is the figure-eight diagram that he drew repeatedly throughout his career, showing the perpetual movement of day into night. The second is his drawing of the half-sun, half-Medusa face. The Libra is known to be attracted to beautiful things, beneath which are housed more violent and monstrous undertones. Libras are also governed by logic, stemming from the Greek concept of Logos. Le Corbusier manifested his desire for Logos with his use of the golden ratio. With a balanced sense of self, Libra men are often in touch with their feminine side. Le Corbusier’s Modular Man was tall and thin, like Corbusier himself, with angular shoulders countered by large feminine hips, reminiscent of prehistoric Mediterranean female fertility Venus statues. The desire for proportion, rhythm and order is also played out in the influence of music on Le Corbusier’s work, particularly that of the composer Iannis Xenakis, who worked in his office. Le Corbusier often borrowed from his “friends” and “colleagues”. The glass surfaces of La Tourette were derived directly from a Xenakis score. With the romantic and meandering desires of the Libra, Le Corbusier explored the most vivid imaginings of the free plan, which began with the Domino House and culminated in his Maison series.

Le Corbusier’s more composed rectilinear exteriors are contrasted by an internal explosion of free form on the inside, which relates to the body of the inhabitant as one moves throughout the space. The acoustic effects as people move through the interiors of Le Corbusier’s spaces relate his architecture to music. Le Corbusier dabbled in Eastern mysticism but it was with his trip to India that his work changed dramatically in this regard. Moving away from the rigidity of Greek Doric structure, he encountered the more ancient female fertility divinities of Mother India. He became interested in Jantar Mantar as a scientific observatory and celestial sanctuary, as it combined the Libra’s need for rational order and cosmic romance. Ronchamp is not unlike an observatory with its small windows that function like apertures, funneling light through thick walls and flooding the interior with light from the heavens. The grounds of Ronchamp are landscaped with grassy earth mounds linking the chapel to the cult of the prehistoric Mediterranean matriarchal goddess. The bell tower of Ronchamp is phallic in form, possibly referring to the Indian Lingam, used in Hindu ceremony to represent the deity Shiva. The Lingam is a symbol of the phallus and represents male creative energy while the chapel, with its womb-like interior, perhaps refers to the Yoni – the vessel that holds the Lingam and represents female creative energy. Ronchamp seeks the Libra’s need for balance between the male and female body. The interior of Ronchamp holds three shrines, each dedicated to an important female image. One shrine is dedicated to the Virgin Mary, another to Le Corbusier’s mother, and the third to his wife. Le Corbusier’s fascination with the bull, which took form in the Chandigarh Secretariat Building, represents an interest in the return to the matriarchal pre-Greek, Cretan and Minoan culture, where the bull was worshipped as a fertility symbol.

Dan Graham, Jessica Russell

Architecture/Astrology, London, Koenig Books, 2014

(Passage quoted in extenso)

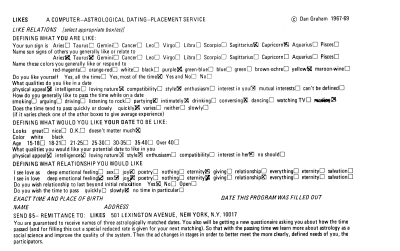

Michael Sanchez — In 1969, Dan Graham completed Likes (A Computer-Astrological Dating-Placement Service), which anticipated online dating services by using a computer algorithm to match potential partners on the basis of astrological signs, physical appearance and relationship priorities. The program even incorporated user feedback, via newspaper advertisement, on the success or failure of matches already made. (“Pandora’s Black Box : Algorithms of Taste”, Artforum, Vol. 50, No. 7, March 2012).

Dan Graham, Likes (A Computer-Astrological Dating-Placement Service), printed matter, 1967–69. Courtesy of the artist, New York.

Corinne Diserens — In the 1960s Graham created several advertisements that were published in magazines and newspapers, including Likes (A Computer-Astrological Dating-Placement Service), 1967–69, which was first designed by George Maciunas. Published in the Halifax Mail Star on October 11, 1969, it was also presented by the artist on a local cable television’s public-access station in Halifax within the framework of his teaching at Nova Scotia College of Art. It was exhibited the same year in 555,087 at the Seattle Art Museum. Dan noted in End Moments (1969): “This year I re-wrote [Likes (A Computer-Astrological Dating-Placement Service)] to make a current interest, astrology, a part of its workings and showed it in Seattle in an exhibition of ‘concept art’ which Lucy Lippard and Seth Siegelaub organized.”

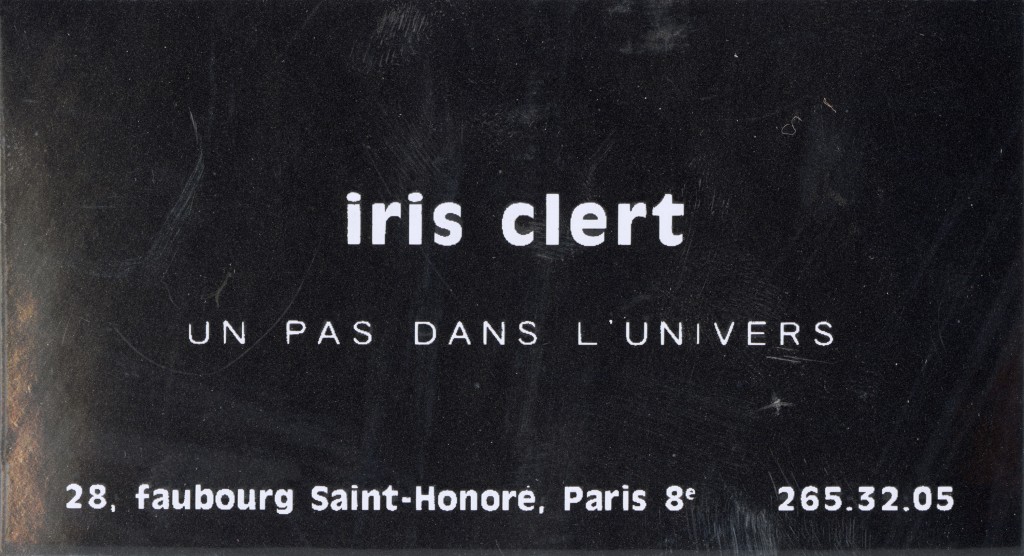

Margot Sanitas — This little piece of reflecting silk-screened plastic is a physical artefact from the world of Iris Clert – Greek-born Parisian gallerist and socialite, artistic talent discoverer and stalwart of the 1960s avant-garde. Like many invitations she designed in various media, it is a good illustration of her advertising acumen. It was Clert’s idea, by the way, to use the infamous IKB (International Klein Blue) stamps (infamous because Klein had to bribe the postal service to accept the fake stamps) on all the invitations to Klein’s show sent out to her wide network of followers and art lovers. The invitations were printed by Monsieur Lapied, “an obliging, understanding printer”, on rue Monsieur-le-Prince. Clert “spent hours on the premises”, she wrote, “composing” her innovative invitation cards, assisted by model maker Robert Brûlé with his “unfaltering artistic taste”. She was also behind the production of a limited series of sardine cans on which the word “Full-Up” invited the public to Arman’s Le Plein show (Full Up, 1960).

Her own business card was a veritable communication tool, reflecting the woman more than the art dealer, whose gallery address is given discreetly in small letters at the bottom under the capitalized phrase “Un pas dans l’univers” (A step in [to] the universe). So one can’t help wondering whether the card isn’t more about celebrating Iris Clert herself, just as she celebrated the artists represented by her gallery.

This precious information tool, passed from hand to hand, is a key that unlocks the door to her personal cosmos. Inevitably it resonates with Yves Klein’s thought and reflections on space and on pictorial sensibility, which, he declared in November 1960, “exists outside of us, and yet still belongs to our sphere !” Un pas dans l’univers also seems perfectly illustrated by two photographs shot in January 1961: they show Yves Klein, one from the front, one from the back, taking a step into his Raum der Leere (Void Room), presented at the Museum Haus Lange in Krefeld, Germany, in January 1961.

The use of a reflective surface for Clert’s business card suggests a form of dematerialization evoking at once the sky, the void and space. The viewer is soon confronted with their own reflection in the card, and cannot help seeing an analogy between this “step” (into Clert’s universe) and the Saut dans le vide (Leap into the Void) on October 19, 1960, at Fontenay-aux-Roses, by Klein, whom Clert affectionately called the “Dictator Baby” !

In 1961, Clert left Paris’s 6th arrondissement. After more than six years spent in 20 sq m at 3 rue des Beaux-Arts, where she’d held several now legendary exhibitions, including Klein’s Vide (Void, 1958) and Arman’s Plein (Full Up, 1960), the ambitious gallerist made up her mind to expand, for which purpose she moved to the ultra-posh 8th arrondissement. On May 15, at 28 rue du Faubourg-Saint-Honoré, she opened an exhibition billed as a tribute to herself : The 41 present Iris Clert, an opportunity for her to be portrayed by all the artists she represented, including Yves Klein, Arman, Jean Tinguely, Raymond Hains and Gaston Chaissac, her fellow Greeks Minos and Takis, and fellow Americans Robert Rauschenberg and Ad Reinhardt. This event set the mood for the years of artistic creation to come. The new gallery was conceived of as a place of life and experimentation, a celebration of her protégés and her successes. She thought of her protégés as satellites gravitating around her solar personality. This radiance may have eventually forced some of the men in her entourage to move to a safer distance for fear of being eclipsed by their friend’s dazzling personality. Clert recalls what Jean Tinguely once said to her : “You know, Iris, the reason I left you is that you’re not an art dealer. I was jealous of you because you’re an artist.”

During the Piccola Biennale she organized in June 1962 in a Venetian palazzo overlooking the Grand Canal, her compatriot Takis took issue with the banners outside saying “Iris Clert à Venise”: “My name – where’s my name ? It doesn’t say my name anywhere, just yours ! So YOU are the star once again ? !” At her Biennale Flottante two years later, American artist Harold Stevenson made a scene for the same reason. Iris Clert made it perfectly clear to him : “I am the face of the brand.”

Above and beyond the explicit reference to the small world she had built around her gallery, Un pas dans l’univers suggests a different cosmological dimension. Clert has never concealed her interest in – if not obsession with – astrology. Before taking any important decision she would consult her personal astrologist, Elzine Privat, widow of the illustrious radio journalist and astrology buff Maurice Privat.

Iris Clert — Elzine was a lovely old lady, full of kindness and tolerance for human frailties. From our first contact there was a huge current of affinity between us, and that affinity became affection. Elzine was to become my teacher, confidante and adviser, especially in the hardest times of my life, and for ten years to come. She kept sacred her husband’s library, which comprised very rare books about astrology in every different civilization. Although she was destitute, to the end of her life she refused to sell her treasures. Elzine drew up my birth chart. I learned that my life was shaken by oppositions, with trines and squares teeming on my chart, but also that I was going to become famous by bringing about a revolution in art ! That I had phenomenal ideas that needed to find expression and that I should follow my inclination to SWIM AGAINST THE TIDE ! I also learned that I would always have financial woes, since my portion of Fortune was affected by Mars, but that it would be saved in the nick of time by Uranus. On the other hand, my Venus, being in the seventh house of Pisces, would be beneficial to those who approach me. As for my sentimental life, it would always be tumultuous. I was very flattered to learn that my ascendant is in conjunction with that of Louis XIV, which explains the arts, luxurious tastes and passions.

Iris Clert

Iris-Time: L’Artventure, Paris, Éditions Denoël, 1978

(Passage quoted in extenso,

our translation)

Margot Sanitas — It was out of the question for the gallerist to open a show or make an important purchase on a date of ill omen. Her correspondence with American artist Ad Reinhardt regarding the preparations for Immobile Forces, a show to be held in Paris in June and July 1963, points up her close connection to astrology, even in the date chosen for the vernissage. In her letter of April 18, 1963, for example, Clert writes : “Please send me your exact date of birth and, if possible, the exact hour. It’s urgent.” A week later, on April 25, she reports on her consultation with Elzine Privat : “Just phoned my astrologer, she told me the 8 th or 10 th of June. So hurry up, otherwise the next good date is the 18 th, too late!!!” (Iris Clert’s letters to Ad Reinhardt, April 18 and 25, 1963 ; Ad Reinhardt papers, Washington, D.C., Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution). Or the date she picked to open Yves Klein’s famous Void exhibit, to coincide with his thirtieth birthday on April 28, 1958.

Iris Clert, a key player in the art world and faithful friend of the 1960s Paris avant-garde, was alternately guide, fortune-teller and even magician. She championed a veritable vision of the art to come, always a step ahead of her time. Another of her business cards, this one monochrome red, was composed around Ad Reinhardt’s encomium “The most advanced gallery in the world”. The American artist, with whom she had a privileged relationship for seven years, affectionately dubbed his dealer “Mystical Iris”.

Iris Clert

Iris-Time: L’Artventure, Paris, Éditions Denoël, 1978

Yves Klein

Dimanche: Le Journal d’un Seul Jour. November 27, 1960, Paris, Festival d’art d’avant-garde, 1960

Ralph Rumney (ed.)

Iris Time and Life: Mémoires Sonores d’Iris Clert, Paris, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, undated

Rosa Bonheur — When I came into the world on rue Sainte-Catherine in the good city of Bordeaux on March 16, 1822, there were no astrologers by my cradle to cast my horoscope. But after moving to By [Château de By in Thomery, Seine-et-Marne], I grew fond of watching the course of heavenly bodies and curious to know how the stars were aligned at my birth.

I learned that the heart of the sky was occupied by the beneficent sign of Aries and that Mars majestically presided. That augured well for me, it seems, for, without knowing that circumstance, I began my artistic career painting sheep. My independent character may be owing to the Ram’s influence, thanks to which I ended up surmounting all the obstacles the stars had foretold : for the foreboding sign of Sagittarius could be seen in the east, rendered all the more formidable by the equally ominous sign of Taurus, a symbol of blind fury, appearing in the west. The sun was in that sign ; the moon, entirely on the wane, was right near it, as was Venus. This unfortunate configuration would have paralyzed my development, for Venus, a planet devoted to grace and love, was under the special dominance of Saturn, the star of the malicious and the jealous. Had I married, I would have fretted no end about my inner life, as my mother did. What saved me was the intervention of Mercury, god of commerce, who happened to be in conjunction with Pollux, one of the noblest stars in the sky.

Anna Klumpke

Rosa Bonheur: Sa Vie, Son Œuvre, Paris, Ernest Flammarion, 1908

(Passage quoted in extenso,

our translation)

Christian Besson — Villa Magica Records. Founded in 2003 by John M. Armleder, Sylvie Fleury and Stéphane Armleder (John’s son), the label has released over thirty albums of mostly Christmas songs that go together with the Christmas party the trio throw every year in Geneva. Stéphane Armleder recalls : “We started by putting out Christmas albums, without any specific plan, because my father and Sylvie Fleury loved that music.” Besides his penchant for Christmas carols, John is keen on the music of Spike Jones and Hawaiian guitars (as played at his big 2006 installation at Mamco, Geneva, Too Much is not Enough).

Villa Magica. The label was named after the house that became the home of John M. Armleder and Sylvie Fleury in the early 1990s. (Fleury still lives there.) Located at 1 rue du Moléson in Geneva, the house used to belong to Adolphe Blind, who bequeathed it to his daughter, Élisabeth. Word has it that Blind, born in 1862 to Genevan grocers, made a fortune installing gaslights and retired in 1899 to devote all his time to magic. Known to the world by his pseudonym Professeur Magicus, he invented or perfected 4,924 magic tricks, according to his own painstakingly kept list, and built or refined a number of magic contraptions and automatons in the basement of his house. He was a polyglot who corresponded with various compeers around the world, including world-famous Harry Houdini (who paid Blind a visit at his villa). On August 25, 1925, at the age of sixty, Adolphe Blind died while performing the magic Egg Bag Trick for some children. His local colleagues then founded the Club des Magiciens de Genève, the first Swiss magicians’ society. Madame Blind, his widow, and their daughter Élisabeth, alias Magiquette, were among the club’s founders.

Professeur Magicus’s substantial collection of conjuring contraptions and literature about magic (over 1,700 titles), displayed at the 1991 magic convention in Lausanne, was subsequently scattered to Paris, New York and Berlin from 2004 to 2009.

“Conjuring is the art of amusing oneself by amusing others”, Blind used to say (as reported by Alfred Chapuis). And with wands and pointed hats we are not far from the aesthetic of party novelties and Christmas ornaments cherished by John M. Armleder.

Ecart Publications. The vignette of the label Villa Magica Records symmetrically corresponds to that of Ecart Publications. While the former schematizes the facade of the rue du Moléson villa, the latter is more in the style of the old cul-de-lampe used by publishers or of schoolchildren’s stamps – a style prized by Fluxus, but also by the College of ’Pataphysics.

We won’t recapitulate here the history of the Ecart group and gallery (6 rue Plantamour), a label John perpetuated with his annual stand at the Art Basel fair and the eponymous publishing house. Ecart’s Double Sphinx series, which dates from 1973, borrowed its imagery from a fortune-teller’s advert in a magazine, which had added some stars itself to an iconography of Egyptian origin. (The Journey of Death, or Journey of Hidden Gates, began at the Sphinx, whence two roads opened towards the underworld. Doing double service as pilot of the celestial bark, the Sphinx was often depicted as a dual figure.)

The Double Sphinx series originally comprised artists’ books (by Lucchini, Armleder, Minkoff, Olesen, Nanucci, Garcia et al.) with small print runs of 250 copies. The vignette hasn’t changed. It was originally printed using offset or silk-screen techniques by Ecart printers, based in the cellar of the Hotel Le Richemond (est. 1875 by John’s great-grandfather Adolphe-Rodolphe Armleder).

The twinned nature of the two vignettes is reinforced by the closeness of the themes of magic and fortune-telling, and the little stars go quite well with the magician’s wand, too.

The address. John M. Armleder no longer dwells in Villa Magica.

John Armleder, Team 40 (eds.)

Yellow Pages, Geneva, Ecart Publications ; Zurich, JRP/Ringier, 2004

Adolphe Blind

Les Automates Truqués, Geneva, Éditions Charles Eggimann ; Paris, Éditions Bossard, 1927

Marcel Broodthaers — Manzoni is dead, physically dead. He was young. Is there a connection between this premature death and the artistic attitude he adopted ? The humor he espoused certainly isn’t a comfortable position to take. And if that was indeed the cause, our questioning of artistic events, of all events, will be profound. Of course Manzoni will be in the terrible book of the 20 th century. (“Beware the challenge ! Pop Art, Jim Dine and the influence of René Magritte”, Journal des Beaux-Arts, No. 1029, November 14, 1963).

Jean-Baptiste Delorme — Broodthaers’s remarks could just as easily apply to himself in anticipo, for his artistic career (1963–76) was as brief as it was crucially caustic. Broodthaers was a prophet who would never abolish the element of chance, a Belgian-style Fate : witness his Salon Noir, a prophetic “decor” from 1966. Invited along with five compeers to exhibit in Philippe- Édouard Toussaint’s gallery/house (Des Salles/Räume, Galerie Saint-Laurent, Brussels, July 9–September 15, 1966), Broodthaers turned the room assigned to him into a mortuary in which he staged the funeral of the poet Marcel Lecomte, a friend from the Brussels Surrealist scene and specialist in the occult, who happened to be still very much alive at the time.

“Word has it that Marcel Lecomte, aghast at Broodthaers’s idea of shutting him up in a coffin, asked for some time to think it over,” writes Stéphane Rona. “He purportedly consulted his tarot cards and then agreed.” (“Le Salon Noir de Marcel Broodthaers”, +-0, No. 16, February 1977). He agreed to his symbolic entombment, represented by an open coffin lined with shelves, which was built by a worker at the Palais des Beaux-Arts after the undertakers first contacted by Broodthaers begged off for reasons of professional ethics. On the shelves inside : thirty-five emptied jam jars through which could be seen Lecomte’s profile in positive and negative photographic images. Next to it : a table covered with black fabric upon which was enthroned a glass globe filled with silver relics. Broodthaers placed his card on the table. It states nothing but the artist’s name in capitals, in a typeface he frequently used at the time for his invitation cards – whose dimensions, by the way, were often similar to those of a business card (6.5 × 9.5 cm for the invitation to the Salon Noir). The top right corner of the card is dog-eared as per proper etiquette when the family of the deceased are absent. And so it was that Broodthaers produced a vision that would be borne out only a few months later : Lecomte died unexpectedly on November 19, 1966.

Marcel Broodthaers posing with the cover of Marcel Lecomte’s coffin for Le Salon Noir, Objet, b/w 16 mm film, 1967.

© Succession Marcel Broodthaers / 2023, ProLitteris, Zurich

The soothsayer artist, on the other hand, was not surprised by Death, full knowing he was condemned by a disease of the liver. His tombstone itself is a work of art. Designed by his wife, Maria Gilissen, it condenses all of his motifs, rather like Duchamp’s Box in a Suitcase, but forever sealed shut to the noise of his self-penned epitaph : Ô Mélancolie, aigre château des aigles (Oh Melancholy, bitter castle of eagles). Fascinated by uncanny coincidences (e.g. the deaths of Charles Baudelaire in August 1867 and René Magritte in August 1967), Broodthaers died on January 28, 1976, his fifty-second birthday.

Berthe Bernage

Convenances et Bonnes Manières, Paris, Éditions Gautier Languereau, 1951

Manuel Borja-Villel, Christophe Cherix (eds.)

Marcel Broodthaers, New York, MoMA, 2016