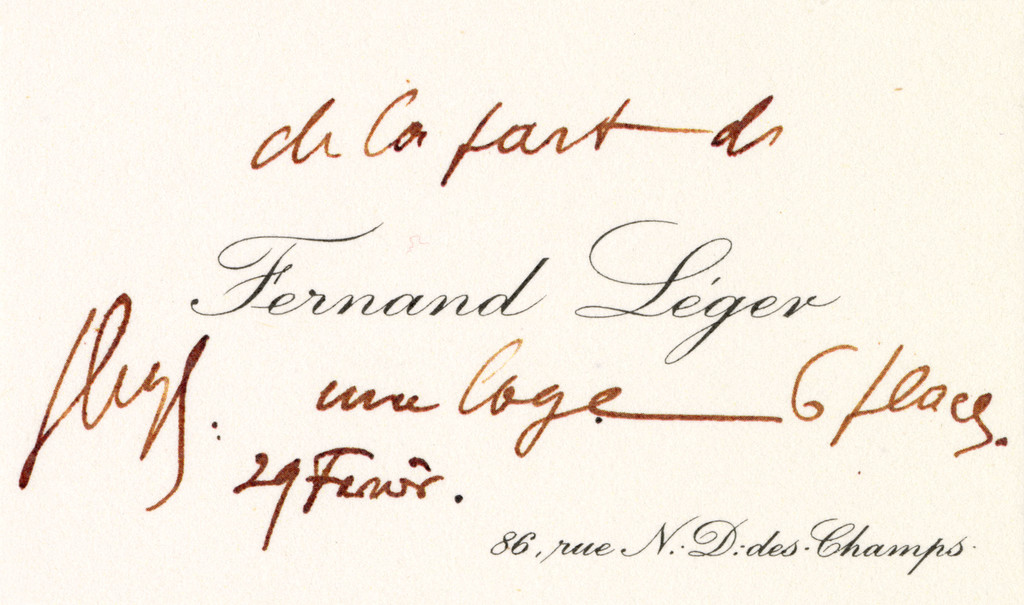

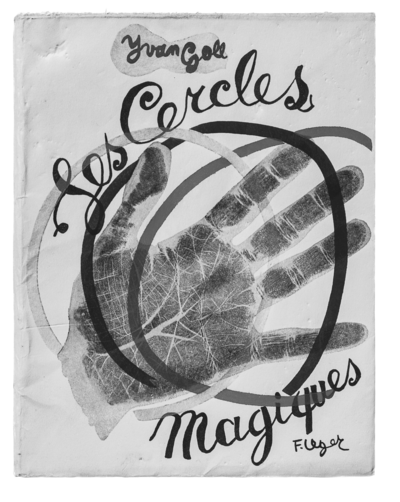

However, when this “voucher for one free entry” – the equivalent of a theatre or concert ticket – reached Léger’s home, the collective hope for a mathematics of Cubism was more or less over. While, from February 5–28, 1919, the Galerie de l’Effort Moderne had presented the first one-man show of Léger’s recent works, Picabia was driving around in a brand new Mercer he’d just had shipped over from New York. He had not exhibited anything in Paris since 1914 so he took advantage of the Salon d’Automne, held at the Grand Palais from November 1 to December 10, 1919, to present four new paintings. He now opposed the deliberate reification of his pre-1914 works of Orphic Cubism with mechanomorphic drawings he had purposefully and repeatedly made since 1915. He also published the first Parisian issue of 391, the magazine he founded in 1917 and would continue to publish until 1924.

The day that the postal service forwarded his note to Léger’s studio, Picabia no longer lived at the address shown on his visiting card. The vast apartment located at 3 avenue Charles-Floquet, a tree-lined artery in the 7th arrondissement of Paris that runs parallel to the Champ de Mars and next to the Tour Eiffel, was now only occupied by his spouse Gabrielle Buffet and their four children, including Vicente, born on the September 15, 1919. Marcel Duchamp stayed in Paris from August to December, and found both board and lodging there, as well as Gabrielle’s continued friendship. Picabia was now residing in an apartment he shared with journalist Germaine Everling at 14 rue Émile-Augier (today rue Jean-Richepin), in the 16th arrondissement. Having met in 1917, his new partner also gave birth to a child, Lorenzo, on the January 5, 1920. On that same day, a twenty-four-year-old André Breton arrived unannounced. He had come to urge his elder to contribute to Littérature, the magazine he had founded with Louis Aragon and Philippe Soupault.

Twelve days later, a tiny paleo-punk with a monocle and a Romanian accent moved in to this very same apartment ; his name, with its dental fricatives, crackled like a taunt : Tristan Tzara. Picabia had met him a year earlier at the Kunsthaus Zurich, during the Das Neue Leben, Erste Austellung. They had exchanged an abundance of letters from 1918, before actually meeting after Picabia – who had come first to Bex then to Bégnins to treat a depressive episode – published in Switzerland three of Tzara’s collections in a row : Poèmes et dessins de la fille née sans mère, followed by L’athlète des pompes funèbres then Râteliers platoniques. Tzara wrote to express his admiration, then offered to collaborate on the magazine Dada – which he did.

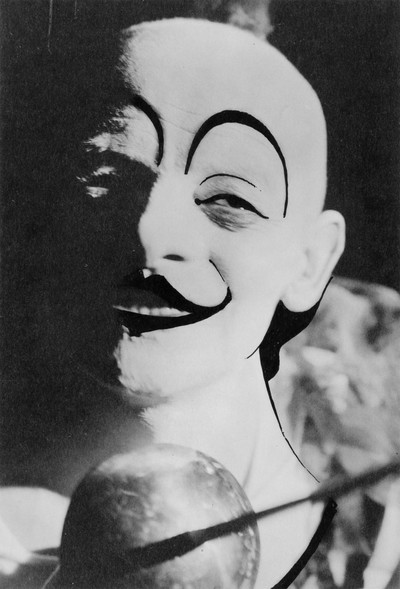

At once an actor, a theoretician and a propagandist for the movement that emerged in the spring of 1916 out of the activities of the Cabaret Voltaire, located at the Spiegelgasse in Zurich, it was his dazzling Dada Manifesto 1918 that truly brought Tzara to the attention of his Parisian counterparts. Because his prose was seen as endowed with the gift of immediately withering what only yesterday would have passed for being highly subversive, he was welcomed as a new Rimbaud. Some were amazed, others irritated. In its September 1919 issue, the Nouvelle Revue Française took the Dada movement to task. Tzara gave a counter response the following December in the columns of the magazine founded by his exact contemporary and future rival, Breton. With this done, Paris could now witness the start of what Aragon would call the “Dada Season”.

The spring of 1920 would see a regular succession of events put on by the movement. First, on the February 5 for the Salon des Indépendants at the Grand Palais ; then on the February 7 at the Club du Faubourg ; and then an event on the March 27, held at La Maison de l’Œuvre in the Salle Berlioz – which Fernand Léger did not attend –, that opened its doors at 8.15 pm, just as Picabia’s handwritten note had specified. This latter event was located at 3 cité Monthiers, not far from 55 rue de Clichy in the 9th arrondissement of Paris, where a scandal had already been provoked by the premiere of Alfred Jarry’s Ubu roi on the December 10, 1896. Orchestrated by Tzara, who intended to re-create, in the manner of the Cabaret Voltaire, this collusion between stage and audience so typical of traveling theatres, the event comprised three parts and counted nineteen performers. Ticket prices went from 3 to 20 francs, and it is still a mystery what rules were applied, whether conventional or not, in establishing the pricing pyramid that night. Only Musidora (the unforgettable Irma Vep in Feuillade’s Vampires, the first film “series” in the history of French cinema), Marguerite Buffet (pianist and Gabrielle’s cousin) and Hania Routchine (opera singer at the Vaudeville theatre) were professional performers. All the others (artists and poets) performed as amateurs offering a variety of delights. Six Dada manifestos were presented to the audience that night, penned by Picabia, Ribemont-Dessaignes, Soupault, Tzara, Aragon and Éluard. Various sketches, mini-dramatizations, monologues and other musical interventions were mixed together. Tzara played himself in his Première aventure céleste de monsieur Antipyrine (The First Heavenly Adventure of Mr. Antipyrine), while Breton read out Picabia’s Manifeste cannibale (Cannibal Manifesto) saddled with a sandwich board :