Next to the frame holding Kosuth’s Flaubert, I have Blu-Tacked a sheet of paper bearing the phrase “Five words in a line” (1930), by Gertrude Stein, the American avant-garde writer and modern art collector who made her life in France, which I plucked from a self-descriptive poem of hers. Stein was an earlier follower of Flaubert, but few see Stein and her matronly bulk as a link in the chain of artistic paternity between the two great men. Her extraordinary persona and relationships with other luminaries of her time (the artists, writers, composers, critics, collectors, aristocrats, and all of their companions who frequented the Steins’ salon at 27 rue de Fleurus in Paris) tend to overshadow her own experimental literary and artistic contributions.

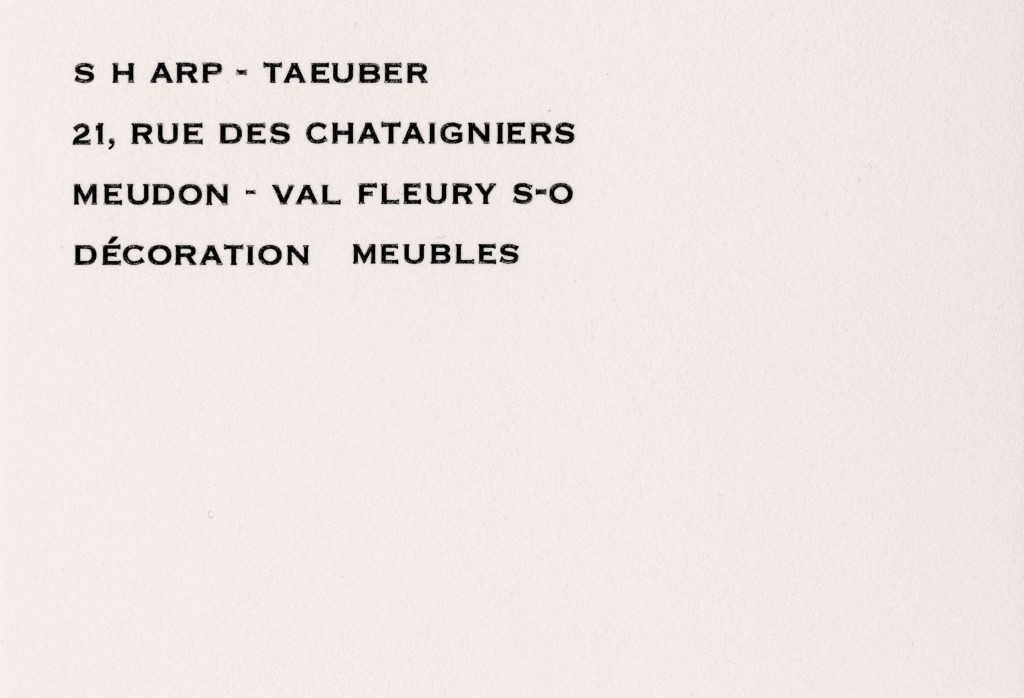

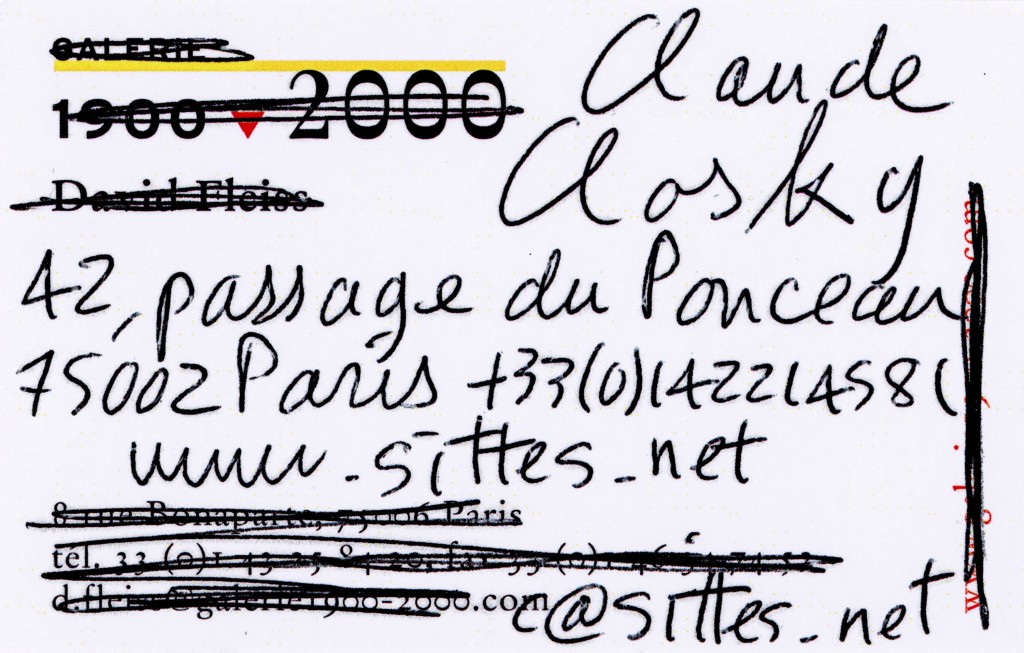

Addressing her calling card sins in that direction once again. As a facilitator of relational aesthetics, the card instantly calls to mind two of her most compelling and historically significant affiliations. The first is Alice B. Toklas (her life partner, secretary and editor – otherwise known for her cookbook incorporating Brion Gysin’s recipe for Hashish Fudge), who is the ostensible subject of The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (1933), the biography Stein actually wrote about herself. The second is Pablo Picasso, who needs no introduction.

Picasso met Stein first. Gertrude and her older brother Leo Stein were the young Spaniard’s first serious patrons in Paris, and this was decisive for his career. Gertrude’s personal exchanges with Picasso went on to form a major strand in the intertwined histories of modern art and literature, in which her visiting cards play a symbolic role. The first work to consecrate their budding complicity was Picasso’s famous Portrait of Gertrude Stein (1906, MoMA, New York), for which Stein recalled sitting “ninety times” in the painter’s Bateau-Lavoir studio. Picasso had the pretension to rival the groundbreaking portraits already hanging in Gertrude and Leo’s atelier-living room at 27 rue de Fleurus, namely Henri Matisse’s Woman with a Hat (1905) and Paul Cézanne’s Portrait of Madame Cézanne with a Fan (1878–88), and Stein’s androgynous figure proved the perfect vehicle for his own breakthrough. Synthesizing elements of works by the French masters before him (such as the impassive, cock-eyed gaze of the Steins’ Madame Cézanne, and the hefty, masculine, forward-leaning pose of Ingre’s Monsieur Bertin in the Musée du Louvre) with the hieratic simplification learned from Iberian sculpture, Stein’s portrait, with its mask-like face, is considered the doorway to Cubism.

Stein tells us that during the poses for her portrait and on her long walks home from Picasso’s studio to the rue de Fleurus, she “meditated and made sentences”, devising her own work, mirroring his creation. She, too, took Madame Cézanne’s plain, solid features and Cézanne’s neutral, non-dramatic technique as a starting point and, having begun to translate Flaubert’s Three Tales “as an exercise in literature”, “she looked at [the portrait] and under its stimulus she wrote Three Lives”, her first book. Three Lives is a trilogy of novellas based on the lives of three working-class women : two white servants (reminiscent of the maid in Flaubert’s “A Simple Heart”), and a young African-American woman, Melanctha, whose complex struggles with race, gender, sexuality and mental health are communicated in Stein’s new, repetitive, stream-of-consciousness style.

Stein saw her exchange with Picasso as the beginning of a whole new era in art, of which they were the two heroes. She summed it up as follows, in Toklas’s voice : “It had been a fruitful winter. In the long struggle with the portrait of Gertrude Stein, Picasso passed from the Harlequin, the charming early Italian period to the intensive struggle which was to end in Cubism. Gertrude Stein had written the story of Melanctha the negress, the second story of Three Lives which was the first definite step away from the nineteenth century and into the twentieth century in literature.”

Picasso gave her portrait to Stein, and in 1909 she reciprocated by writing a word-portrait of him, “Pablo Picasso”, the likes of which had never been seen. To her delight, it found a publisher in the ultramodern photography journal Camera Work in 1912.

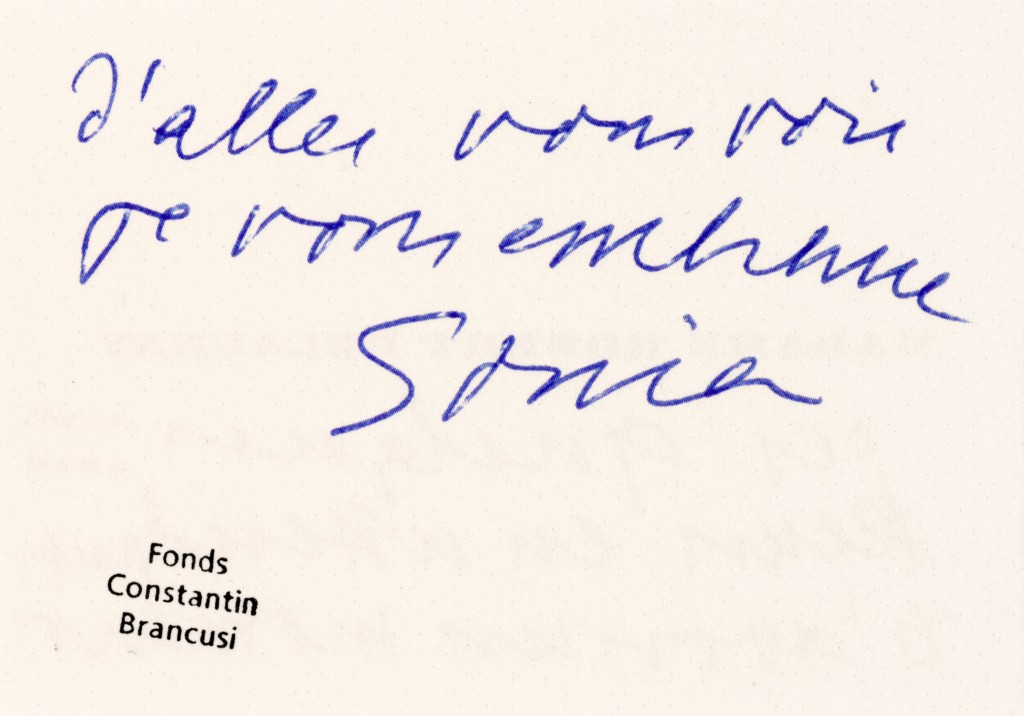

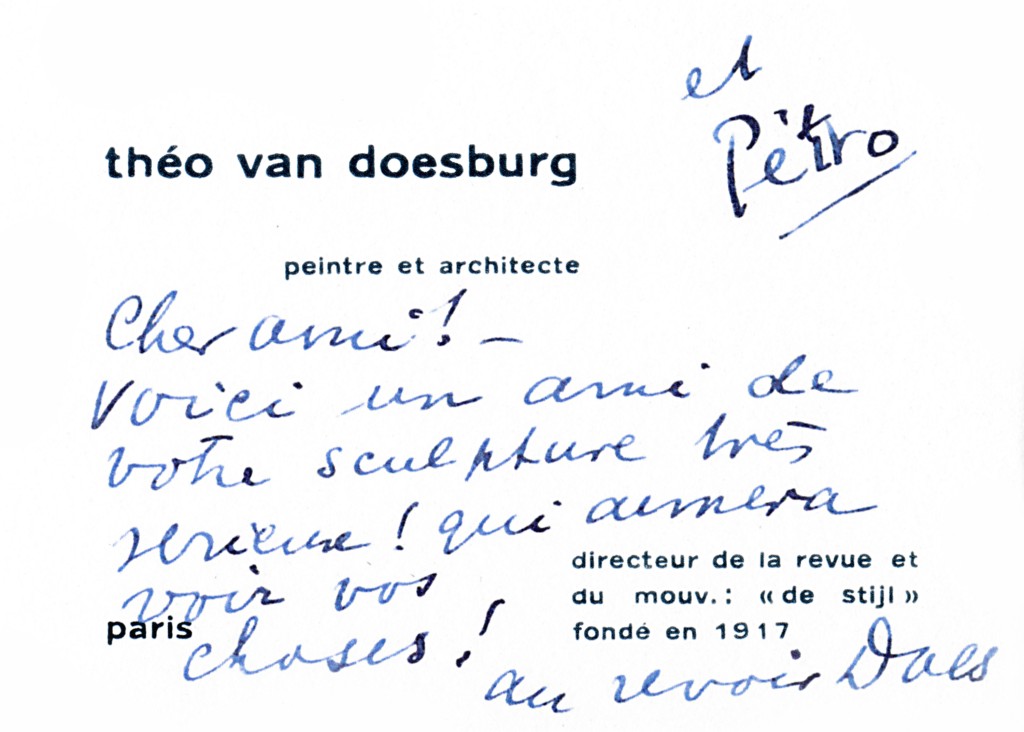

Stein’s maiden calling card, which reads “Miss Gertrude Stein”, enters the picture at exactly that time. Speaking again as Alice (who moved in with her and Leo in 1910), she explains : “One day we went to see [Picasso]. He was not in and Gertrude Stein as a joke left her visiting card. In a few days we went again and Picasso was at work on a picture […] and at the lower corner painted in was Gertrude Stein’s visiting card.”

The painting Stein’s card completed was The Architect’s Table (1912, MoMA, New York), a large oval still life in shades of brown and gray, made in his new, Cubist Analytic style. Stein’s name and other words seem to float on the surface of its hermetic diffraction of forms – Picasso’s personal stories rising to the top of his formal experiments – while the white rectangle of her card is wholly there at the base of the picture, testifying to her presence in his life and work, promoting her.

By seductively inscribing Gertrude’s card into The Architect’s Table, Picasso seems to have tipped the scales definitively in his favor, against her brother Leo. Gertrude and Leo (who always purchased paintings jointly from their family trust fund allowances.) had in fact stopped buying Picasso’s work by 1910. Leo had lost interest in the direction he was taking, and in his opinion, both Analytic Cubism and his sister’s Cubist-aligned verse were similarly stupid “Godalmighty rubbish”. Gertrude purchased the painting by herself, paying the Kahnweiler gallery in two installments. This independent acquisition launched her as a collector in her own right, and Leo decamped to Italy in early 1914, leaving the apartment to Gertrude and Alice, alone at last.