As an even younger man, when he worked for the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Sion, Switzerland, he saw that restaurant lunches were “overpriced and under par” so, despite not knowing how to “boil an egg”, he figured it would be better to cook for everyone at home.

Charlotte Magnin — Parisian restaurants and cafés are places of social mixing and exchange par excellence, a locus of effervescence and conviviality where people from all walks of life come together, a diverse crowd with diverse interests. The mysterious Eclectics Society, founded on April 8, 1872, by Aglaüs Bouvenne (1829–1903), convened at good restaurants on the Left Bank, Chez Deluc (rue de Seine) or Chez Laffite (rue Taranne, which was subsumed in the creation of the boulevard Saint-Germain), the famed haunts of artists and their creative circles.

The Eclectics Society was a cheerful, noisy bunch who met monthly for dinners and lively conversation. The sole prerequisite for admission into this secret society was an interest in the arts : its members comprised a motley mosaic of literati, painters, engravers, poets and bibliophiles. Ruminating and imagining out loud, debating, harping on trivialities or rambling onto serious terrain was the order of the day, buoyed up by a dynamic disorder that could praise or pan works in vogue. An artistic laboratory, the society kindled its adepts’ production through unusual publications or through the fanciful composition of invitations to their meetings. Their imaginations would unfurl on the table in the form of texts and drawings like so many literary and artistic extravaganzas on paper. These meetings were to continue into the first years of the 20th century.

Aglaüs Bouvenne, the foremost Eclectic, studied first in painter Narcisse Díaz de la Peña’s studio before entering Joseph Lemercier’s printing shop in the capacity of contremaître du noir in charge of checking the printed proofs. Given his artistic and technical precision, it was only natural for Bouvenne to become a printmaker, employing drypoint as well as etching. His profession as an engraver and his status as an avowed bibliophile formed a perfect alchemy for focusing his interests on the making of bookplates. Whether a mark of the owner’s pride or possessive love, these vignettes skillfully and expressively distill the identity of the collector of the books in which they are inserted. Bouvenne assiduously collected all the bookplates he could find at booksellers’ along the banks of the Seine and among his acquaintances, putting them all together in a collection that was unprecedented at the time. He also produced a number of bookplates for his own personal use or for his entourage. His ex libris play on the owners’ names through the use of an apt allusive image, generally accompanied by a monogram. He often gave pride of place to puns, such as luxuriant vegetation foregrounded on the bookplate for the art critic and novelist Champfleury (literally “flowery field”) or a stylized mosquito for that of bibliophile Jules Cousin (known as “Gnat”).

Bouvenne’s business card employs the same visual wordplay : his shop sign is planted obliquely in the straw seat of a chair, a reference to the street (rue de la Chaise) on which his studio was located. It just so happens that, as though in his memory, a printing and copy shop is housed at that very address today.

Some of his bookplates draw on the collectors’ literary world, as in the Egyptian motifs employed for writer Théophile Gautier, alluding to the latter’s 1858 novel The Romance of a Mummy. Likewise for the ex libris of Victor Hugo, the printmaker’s friend and admirer, depicting the front of Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris. The two iconic towers frame the central body of the edifice, in which Bouvenne placed Hugo’s monogram, itself a mise en abyme of the cathedral’s H-shaped architecture. The powerful image on this bookplate, which dates from 1870, is said to have inspired the poet Auguste Vacquerie’s memorable line : “Les tours de Notre-Dame étaient l’H de son nom” (The towers of Notre-Dame were the H of his name). The printmaker subtly succeeded in visually linking the identity of the cathedral with that of the writer who glorified it.

In his painstaking efforts to collect and produce bookplates, Aglaüs Bouvenne helped to rescue from oblivion a practice on the wane in the 19th century and gave it a vigorous boost. Bouvenne’s drawings are in the service of letters, each of which holds within itself, as he puts it, “imagination, a love of individuality, the attraction of mystery”.

Aglaüs Bouvenne

Les monogrammes historiques d’après les monuments originaux, Paris, Académie des bibliophiles, 1870

Paul Gachet

Le docteur Gachet et Murer: deux amis des impressionnistes, Paris, Éditions de la Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1956

Léon Maillard

Les menus et programmes illustrés: invitations, billets de faire-part, cartes d’adresse, petites estampes: du XVIIe siècle jusqu’à nos jours ; Paris, G. Boudet, 1898

Auguste Poulet-Malassis

Les Ex-Libris français: depuis leur origine jusqu’à nos jours, Paris, P. Rouquette, 1875

Auguste Vacquerie

Mes premières années de Paris, Paris, Michel Lévy Frères, 1872

Fabien Pinaroli — This 1976 visiting card, which reads “N. E. Thing Co.’s Eye Scream Restaurant”, dates from the final years of N. E. Thing Co. (henceforth referred to as NETCO). Created by Iain Baxter& and his wife Ingrid in 1966 as an avowed “critical enterprise”, NETCO’s official name was in fact much longer: I Scream You Scream We All Scream For Eye Scream Parlour Ltd. To my knowledge, this card is from the last batch Baxter ever printed as business associate of his wife.

Eye Scream, a restaurant/gallery, opened in 1976 in Vancouver’s most arty neighborhood. It quickly became one of the trendiest spots in town. NETCO was responsible for its complete design : from the neon art-deco lettering on the aluminum facade, reminiscent of American trucks, to the tableware, which was used in the restaurant as well as being available for sale as works of art (each piece limited to five hundred copies). Following an avowed nominalist bent, the tableware was labeled, in distinctive Eye Scream typography (Sinaloa, designed by Rosmarie Tissi in 1974), “plate”, “glass”, “cup” etc. Iain and Ingrid Baxter, the co-presidents of NETCO, posed for photographs alongside their colleagues covered in whipped cream or parsley, or lying atop a bed of lettuce. Naturally, the titles of these images recall restaurant menus.

According to documents dating from that period, Eye Scream Restaurant’s ambition was to be “a platform for ideas (through images, in discussions, as a movement and in a celebration of the ordinary). For NETCO, it was a vector of change, of culture, of good frivolity, of sensitivity information, of just about any thing.” In the restaurant, while eating a wacky salad, one could admire NETCO prints, photography and lightboxes.

Iain Baxter&, Co-President, N.E. Thing Co., As An Open Faced Sandwich, color photograph, 1977. Courtesy of the artist, Windsor, ON.

Lightboxes at such an early date ? Yes indeed ! The same kind used in advertising, and therefore considered beneath the use by artists. Iain Baxter in his guise of nonchalant co-president of a business of “just about anything”, imported this element : first, in 1965, it was a paintbrush laminated in plastic, placed in a small empty box made from an emergency exit sign. And as early as 1968, NETCO produced lightboxes with Cibachrome prints for their 1969 show at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa : N. E. Thing Co. Environment.

Next door to the Eye Scream restaurant, the N. E. Professional Photographic Display Labs Ltd., another NETCO offshoot, had – if the ad copy is to be believed – been using the only Cibachrome machine in Western Canada since 1974. The lab that Iain and Ingrid built along with an associate became the go-to place for local artists, institutions and businesses in search of Cibachrome prints and lightboxes. When in early 1978 the couple divorced, NETCO and all its offshoots, including the restaurant and photo lab, were discontinued. They sold their shares to their associate, David Honey, who later changed the name of the business and, in the early 1980s, sold the Cibachrome section to none other than… Jeff Wall.

Some of this information was relayed to me by Iain himself, and some of it by French art critic Christophe Domino. The latter also informed me that the hanging of the AGO Art Gallery’s permanent collection in Toronto in 2008 gave pride of place to the story of the origin of the lightbox. In the collection, Nude, a beautiful little NETCO lightbox was placed next to another, larger one, by Jeff Wall called The Goat. The first was from 1968, the second, 1994. The juxtaposition of both works was significant from a historical perspective in that it threw a wrench in many a received notion, as the reaction of the curator of the Tate at Raven Row in London in 2013 shows : upon seeing a NETCO lightbox from the same series in the Iain Baxter& show she said, “I don’t remember having seen anything like that before.” The italics are mine ; they are meant to convey a disdainful tone, for the lady was stunned that such a work could have been created eleven years before Jeff Wall’s 1979 pieces.

Pierre Leguillon — o you know if Gordon Matta-Clark ever had a business card, as an artist or as a young architect, or more precisely for FOOD, the artist-run restaurant he co-founded in Soho with Caroline Goodden and Tina Girouard? If I’m not wrong, FOOD opened in October 1971, at 127 Prince Street in Soho, and lasted for about three years.

Jane Crawford — Thank you for your inquiry, Pierre. I’m afraid that you over-estimated our financial situation in the 1970s! We lived hand to mouth. Business cards would have been seen as an exorbitant luxury – and to whom would we have handed them out ? At Gordon’s death there had been the smallest kernel of an art market for his work. He was known as an artist’s artist because artists were really the only ones who even knew who he was. I’m sure you don’t want to know any of this but it is a very amusing idea. I’m sorry that I can’t help you.

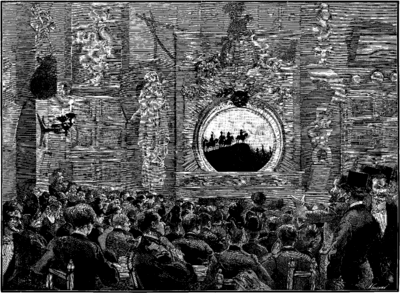

Aurélie Jacquet — “Haaaaaaa.........lte!” Rodolphe Salis’s peremptory call to “Stop!” would ring out at Le Chat Noir cabaret. Thanks to this masterful bonimenteur, this bantering mischievous emcee, the show was never the same from one night to the next. He would toy with his assembled patrons, sniping, shouting, asking them embarrassing questions, adapting to the mood of the crowd. By January 1896, just before the cabaret closed for good, L’Épopée (The epic) had already chalked up a thousand performances, touring cabarets and private salons all over France. Caran d’Ache, the creator of this shadow play, always managed to come up with something new for him. Sometimes as many as thirty, forty, even fifty zinc tableaux, depending on the version, accompanied by the music of Charles de Sivry (1848–1900), le musicien des ombres (the musician of shadows): piano, percussion, sound effects – whatever it took to create the illusion of the great battles and events of the Napoleonic imperial epic.

Back in 1881, when he was still signing his first drawings under his real name Emmanuel Poiré, Caran d’Ache depicted battle scenes in silhouettes as black as shadows against a white ground. Thanks to the 1881 law guaranteeing freedom of the press, cartoons and caricature burgeoned as the number of newspapers and magazines increased apace. Poiré (b. in Moscow on November 6, 1858) adopted the pseudonym Caran d’Ache as a nod to his Russian roots : it is a transcription of karandash (карандаш), meaning “pencil”, a nickname conferred on him by his prehistorian friend Adrien de Mortillet (1853–1931). So it comes as little surprise that, fifteen years after his death, the Fabrique Genevoise de Crayons in Geneva should turn his pseudonym into a brand name for pencils and his signature into a logo, even though he had no special ties to Switzerland.

An illustration depicting Caran d’Ache’s L’Épopée (The Epic) at Le Chat Noir cabaret, Paris; picture drawn from life by Louis Tinayre published in L’Univers Illustré on February 12, 1887. Collection Museum of Mistakes, Brussels.

Le Chat Noir cabaret had not yet moved from 84 boulevard de Rochechouart when artist Henri Rivière came up with the idea of a shadow theater on stilts, which was then built above the garden in the spring of 1885. The backstage area, also called the boîte à sel (salt box), was concealed behind a stretched canvas screen against which back-lit cut-out figures moved on runners laid inside the puppet booth. The sets, lighting, puppets – the whole choreography had to be synchronized down to the last detail to bring forth the magic of shadow theater under the bonimenteur’s direction and, lest we forget, with music accompanying the action from start to finish : songs, blaring cacophony for the explosions, steady rhythms for trotting horses… Each play featured technical innovations to produce increasingly realistic effects for Rodolphe Salis’s little cabaret theater. “The colors, the music, the songs, rounded out the illusion and thrilled the house,” writes Pierre Lefranc.

Its success – the show toured for ten years – was thanks to the combined talents and ingenuity of Henri Rivière and Caran d’Ache. For L’Épopée, which premiered on December 27, 1886, Caran d’Ache created the illusion of moving crowds and depth of field, whilst steadily perfecting the atmospherics on stage. Not a single detail was left to chance : the silhouettes were cut out in perspective (an idea first implemented in Rivière’s production of Georges d’Esparbès’s Roland à Roncevaux), glass was used to produce colored effects, and the zinc plates followed smoothly one after the other. All the stage directions were issued in the wings by means of pantomime. The scene changes had to be carried out with smooth, painstaking precision.

Caran d’Ache had a passion for battles : his grandfather, an officer in Napoleon’s Grande Armée, had been wounded in the 1812 Battle of Borodino and then stayed behind in Russia ; and Poiré himself had joined the army after emigrating to France and designed uniforms for the French war ministry. He resurrected the Napoleonic myth in an age in which all that remained of the emperor in the collective consciousness was a caricature in puppet theatre or on thaumatropes, snuffboxes and waffle irons ! “His silent poem of sliding shadows is the only epic we have in our literature.” (Jules Lemaître, Impressions de théâtre, Le Chat Noir, 1888–1898).

A specific sense of humor took root in fin-de-siècle Montmartre. The first Arts Incohérents exhibition in 1883 at the Vivienne Gallery featured one of Alphonse Allais’s infamous monochromes (long before Yves Klein’s were shown at the Iris Clert Gallery in May 1957), much to the delight of Caran d’Ache, his friend and former fellow comrade in arms, who also illustrated the 1887 publication of Allais’s humorous monologue La Nuit blanche d’un hussard rouge (The white night of a red hussar). Allais’s vignettes marked “a veritable turning-point in the depiction of stories without words. No need to provide long-drawn-out captions or explanations of the pictures anymore : the drawing was sufficient unto itself” (Mariel Oberthür). This captionless concept, still widespread in our day, was seminal to the development of photographic publications. The first novel to be illustrated with photographs was Georges Rodenbach’s Bruges-la-Morte (1892), followed by the likes of André Breton’s Nadja (1928) and, in our day, several of W. G. Sebald’s novels, including The Rings of Saturn (1995) and Austerlitz (2001).

Alphonse Allais went on to say that Caran d’Ache and his team had no idea to what extent they were “making history” at the Chat Noir through their scenographic innovations, which recalled the workings of Louis Daguerre’s Diorama theater back in 1822. (Daguerre was still a painter and stage designer at the time. It wasn’t till a few years later that he helped develop Nicéphore Niépce’s 1916 invention : photography.) Daguerre’s Diorama used complex lighting effects to bring to life his hand-painted 22 × 14 meter backdrops.

The script and score of L’Aigle (The Eagle), an “epic in 12 tableaux” by Eugène Courboin, were published in 1905. Thanks to such publications, anyone could put shadow plays on themselves. They had only to rent or buy from the Mazo publishing house a magic lantern and the colored glass slides needed to bring silhouettes and whole scenes to life between the lights and stretched canvas. As at the Chat Noir, the history of France was subsequently replayed at home.

Mariel Oberthür, Pierre Lefranc, Jérémie Benoît, François Lesure, Laurent Mannoni

Napoléon au Chat Noir, l’Épopée vue par Caran d’Ache, Paris, Musée de l’Armée, 1999

Mark Thomas Gibson — What does a nomadic artist carry to identify himself? Carl August Reinhardt’s striking business card immediately reveals his level of skill as well as his sense of humor and wit. Born in 1818 in Leipzig, Germany, Reinhardt was well-educated and attended schools in Leipzig, Dresden and Munich. Today, the idea of the artist as roving entrepreneur is not just “the norm”, it is what we strive to become. Reinhardt was just this type of artist, traveling and producing in his wake. He was an author, a landscape painter and a caricaturist. Honing these three skills allowed Reinhardt to become, as some have suggested, a pioneer of comics.

During Reinhardt’s time, a popular form of illustration known as Bilderbogen emerged. Bilderbogen were large hand-colored lithographed prints that juxtaposed a series of images. The layout of these adjacent images is essential to the creation of duration in an illustrative narrative structure. The simple visual dichotomy allows for the emergence of a “before” and an “after” and gives the viewer space to imagine what happens in between. Though Reinhardt was not the creator of this format, his abilities in narrative construction and the use of figurative likenesses and settings played a major role in the development of that all too misunderstood art form we now call comics.

When you look at Mr. Reinhardt’s card you can see all his talent on display. He used his card to show off his abilities as a draftsman. His card acted as a tiny salvo to prospective clients, as it passed from his hand into theirs. What you hold is a miniature version of his work and the artist himself, who is seen dressed in a suit and black top hat, riding a wooden painter’s palette. The palette has grown two antennae and the front and rear legs of a grasshopper. Insect wings spring from the back of the palette to complete the metamorphosis. The palette leaps from left to right across the card. Reinhardt tightly clutches a jousting pole under one arm, and holds the bridle strap in his other hand. The small caricature shows the artist as a bespectacled figure with a long nose protruding from his face. The nose runs parallel to the jousting pole held under his right arm, which acts as secondary line of offense should the pole fail him. We see the name of the artist, “C. Reinhardt”, scrawled along his elongated septum, turning his comically large snout into a battle flag as he enters into the fray. What does this calling card say about this particular crusader of image-making ? Well, if we are sensitive to his deft hand and playful wit, his world is one where fantasy in all forms and scales is welcome. This is the card of a journeyman artist, a hired gun, armed with pigment and ink.

Reinhardt would never know the extent of his influence. He eventually settled in the town of Radebeul, where he continued to work as an author and playwright as his health failed him, and opened a restaurant.

![Facade of the restaurant Zum Calculator, named after the title of Carl August Reinhardt’s satiric newspaper, undated [late 19th century], Radebeul. Stadtarchiv Radebeul, Germany. - © Oracles: Artists’ Calling Cards](https://oracles.editionpatrickfrey.com/media/pages/chapters/deal-eleven/mark-thomas-gibson/2871f5e404-1565687734/11-05-reinhardt-hd-ok-400x.png)

Facade of the restaurant Zum Calculator, named after the title of Carl August Reinhardt’s satiric newspaper, undated [late 19th century], Radebeul. Stadtarchiv Radebeul, Germany.

Caroline Coutau — Yan Duyvendak is a curious mix. On the one hand, he is quite the Walserian marginal, capable of feeling such vertiginous joy at being alive that he is consumed with sorrow ; on the other, he is a bold, strategic, effective entrepreneur. His long silhouette is lithe but slender and solid. His get-up-and-go can suddenly wane, but more often than not it is boundless. He is not afraid of rallying eighty people round him for a project or completely overhauling a kitchen – only to redo the whole thing differently six months later. Large-scale projects that ask profound questions –that’s his thing.

So it was that from 1989 to 1992, while studying at the École supérieure d’Art visuel in Geneva, he joined forces with a friend to start up a table d’hôte in his home, quai du Cheval Blanc, the address on his business card. He was twenty-four years old at the time. As an even younger man, when he worked for the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Sion, Switzerland, he saw that restaurant lunches were “overpriced and under par” so, despite not knowing how to “boil an egg”, he figured it would be better to cook for everyone at home. People gave him cookbooks (“I really couldn’t boil an egg”, he insists) and everyone headed over to “chez Yan” for lunch. But in the catering department, his big hit was Le Pôle.

In late 1996, returning to Geneva after a one-year residency in Paris, he didn’t believe in art anymore (such fits of despair would recur from time to time) so he started up a restaurant not quite like the others. It’s true, things were a little easier then than now : some people he knew, actually friends of friends, had a storefront they hardly ever used among the squats of Îlot 13. At the back of the big foyer was a low wall, behind which was a smaller space fitted out with a faucet, a separate toilet, and a door leading to a small courtyard. He bought a gas stove without further ado and had a plumber friend put in a sink. Some benches, tables and chairs were already there.

Then he put flyers wherever interesting and interested potential clientele gathered : at the university and art school, squats and cultural venues. The ad shows Little Nemo entering an igloo with his friends and announces the opening of Le Pôle restaurant with a set menu (2 appetizers, 1 main course) for 10 francs. Open evenings Thursday through Saturday. The first fortnight, patrons were treated to a free dinner if they brought along their own plate, bowl, glass, fork, knife and spoon. Yan had a knack for communication, networking and promotion. And it was up and running.

Patrons trickled in at first. Twenty meals were served the first night. The food was good, so was the wine. Everything was painstakingly prepared and well presented. Within less than a month, I remember leaving the Parc des Cropettes to come upon a line of people waiting to enter Le Pôle : it was now THE place to go. The “public” came without knowing what they would get to eat that night. Thai, Indian, Moroccan, French, Basque, Quebecois… Always impeccable, always tasty, always beautiful to look at. The core team went from three to twenty-one staff. Some did the shopping, others the cooking, the third group waited tables, the fourth washed the dishes and put them away. They were all paid by the hour out of the aggregate profits on the three nights of business per week. Meager wages, but wages all the same. Le Pôle’s patronage soon mushroomed from twenty meals the first night to seventy. “Patrons would come back,” recalls Yan : “Can I have the blue plate with the red hearts on it, that one was mine.” The drama crowd rubbed shoulders there with the art scene, intellectuals with restaurant critics (Yan’s culinary acumen had come a long way since Sion), friends with friends of friends. They did not have a liquor license. “The police would walk past the window and see the booze flowing freely”, the restaurateur remembers, “but no one ever came to investigate.” In late spring, two newspapers listed Le Pôle among the good summer restaurants in town. But then the building was torn down and Yan went back to his artistic pursuits.

I don’t think it’s far-fetched to see the story of Le Pôle as the commencement of the artistic projects he put together subsequently, with various parts to be played by artists, actors, dancers, lawyers, spectators : in a word, real people. Art is, above all, about offering an experience, whether it be a real – albeit alternative – restaurant or an agency interfacing between associations to help refugees, such as Actions, a play he staged in 2016 : the “playbill” was actually a registration form to help refugees : those who signed up could be reimbursed for the price of their tickets.

Pierre Leguillon — Édouard Manet moved into 77 rue d’Amsterdam in the 8th arrondissement of Paris on April 1, 1879. It was the last of eight studios he was to occupy in Paris. And there he would die of syphilis in 1883, at the age of fifty-one.

Located at the back of a courtyard in a building inhabited by other artists, the space was quiet and flooded with daylight. The studio contained some furniture, which Manet sometimes worked into his compositions, and, piled up in a nook, dozens of paintings that would soon be acclaimed masterpieces, including Le Linge (The Laundry), Olympia, Jésus insulté par les soldats (Jesus Mocked by the Soldiers), Argenteuil and Chez le père Lathuille (At Father Lathuillle).

In 1878 Manet began painting a great many scenes of people in cafés, one of the few places where people from all walks of life mix. He would make quick sketches of the regulars, men and women, as well as waiters and waitresses at the Brasserie Reichshoffen in Montmartre or Café Guerbois in Batignolles. Many of these sketches gave rise to full-blown paintings. In The Café-Concert (1878), the density of the clientele is conveyed by cutting several figures off at the edges, as in a photograph. La Prune (The Plum), on the contrary, represents a young woman sitting alone, lost in her thoughts, before a plum soaked in brandy, with an unlit cigarette in her hand. Manet painted it in his studio, where he was known to have a marble-topped bistro table with cast-iron legs. He signed the painting on the marble table amid a decor first believed to be La Nouvelle-Athènes, the café where he would meet up with fellow Impressionists Degas, Pissarro, Monet et al. since the early 1870s, although he did not participate in the events they organized, notably the first Impressionist exhibition, which was held in the former studio of the photographer Nadar in 1874. So their meetings at La Nouvelle-Athènes were as important to the avant-garde artists at the time as the shows they put together with an ever-varying lineup of members of the Société Anonyme des Artistes Peintres, Sculpteurs et Graveurs (Anonymous Association of Painters, Sculptors and Engravers), the Union and the Salon des Indépendants.

In the final analysis, Manet appears to have invented the café he painted here.

In 1881 Manet had a counter moved into his studio to form the foreground for his famous Bar at the Folies-Bergère. Two red triangles on the labels of the British Bass Pale Ale bottles frame an elaborate still life comprising bottles of champagne and Bénédictine alongside a bowl of tangerines.

Huysmans described the Folies-Bergère as “the only place in Paris that reeks so delectably of the makeup of paid affections and the barking of weary corruption”. Suzon, a barmaid at the Folies-Bergère, would go to Manet’s studio to pose for him when she was not working at the cabaret. Shortly before that, Manet had already convinced a waitress at the Brasserie de Reichshoffen to pose for his Café-Concert (1878) and The Waitress (La serveuse de Bock, 1879).

The Bar at the Folies-Bergère was the last painting Manet exhibited at the Salon in 1882. It gave rise to copious criticism in the sequel, and its famously “unfaithful” mirror is still a subject of debate to this day. We see therein the reflection of the crowd at the cabaret, but the mirror simultaneously imparts different points of view and temporalities, as on a movie theater screen. The mirror opens out, in any case, onto the space of the painting itself. During a lecture in Tunis in 1971, Michel Foucault commented on the picture : “Manet certainly did not invent the non-representational painting since everything in Manet is representational. But in his representation he brought the fundamental material elements of the canvas into play, so he was in the process of inventing the painting-as-object, if you will, which was doubtless the fundamental precondition for eventually dispensing with representation itself and allowing the free play of space with its pure and simple, even material, properties.”

In 1979, Jeff Wall produced Picture for Women, a “remake” in the cinematographic sense, placing himself with his camera in front of a mirror in a classroom while a model assumes Suzon’s pose in the foreground. “A kind of classroom lesson on the mechanisms of the erotic,” he said, like the game of seduction in Manet, in which the protagonist is eclipsed in the foreground to make room center-stage for the viewer of the painting. Dan Graham went even further in 1977 with his Performer/Audience/Mirror, a performance video in which the artist describes the “crowd” while they are reflected in the mirror behind him.

But Manet’s studio-turned-café was not confined to the reconstruction of decors in which to place figures for his compositions. His workplace was just as much a hangout for friends, critics and the Parisian demi-monde. Painting in public does not seem to have bothered the artist, and Jacques-Émile Blanche, a young painter and socialite who frequented the studio, even claims “he would have painted amid a crowd at the place de la Concorde as easily as in the midst of his friends at the studio”.

Although associated with bohemianism owing to the scandals caused by Olympia and The Luncheon on the Grass, Manet actually led a rather orderly bourgeois life. He was possessed of an “innate elegance”, wrote Zola, which is well rendered in Nadar’s photographic portraits, especially the one taken in 1874. “Few men were as charming,” wrote Antonin Proust, a friend from his schooldays who was to become his biographer – and was appointed Minister of Fine Arts in 1881. As Pierre Bourdieu observes : “The paradox is that he was a revolutionary dandy.”

Manet, a smooth-talker whose gangrenous leg confined him to the studio, brought in the conversation and ambiance of the cafés he had given up. Madame Manet – although she never set foot there – claimed all the same that the studio had become “an annex of the Café de Bade”, an artists’ stomping ground on the boulevard des Italiens. And Jacques-Émile Blanche recounts that “around five o’clock you could hardly find any room near the artist. On an iron table, a recurrent prop in Manet’s works, a waiter would serve glasses of beer and aperitifs.”

Pierre Bourdieu

Manet: une révolution symbolique: Cours au Collège de France (1998–2000), Paris, Éditions du Seuil, 2013

Françoise Cachin, Charles S. Moffett (eds.)

Manet, 1832–1883, Paris, Galeries nationales du Grand Palais; New York; The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Éditions de la Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1983

David Campany

Jeff Wall: Picture for Women, London, Afterall Books, 2011

Michel Foucault

La Peinture de Manet, Traces écrites, Paris, Éditions du Seuil, 2004

Joris-Karl Huysmans

Croquis parisiens, Paris, Slatkine, 1996

Édouard Manet (et al.)

Manet raconté par lui-même et par ses amis, Geneva, Pierre Cailler, 1945

René Maizeroy — Once you’ve entered Manet’s studio, even for an indifferent visit, you can’t make up your mind to leave. You linger endlessly, smoking cigarettes, chatting, badmouthing your neighbor. Everyone is immersed in exchanging news and gossip, slipping in a word here, a jest there, sparkling with wit and sounding off like fireworks.

Manet soon forgets his model and the painting he has begun. A Parisian through and through, literate, having read and retained a great deal, as skeptical as they come, he sprinkles racy remarks like pinches of pepper on the conversations going on around him. It’s like a funfair where you throw a ball to knock down the dolls arranged in rows inside the stand. What a merciless massacre ! The epigrams gambol and frolic, theories gush forth, puns crisscross the conversation, mocking, boisterous.

Allison Deutsch — Manet submitted a painting entitled Le Bon Bock to the 1873 Salon portraying printmaker Emile Bellot grasping a beer. Le Bon Bock was a critical success, and inspired Bellot to found a dinner club in 1875 called the “Dîner du Bon Bock”, attracting artists and writers to Montmartre for fifty years. The artful invitations to the dinners specialized in humor, as in an 1883 example in which caricaturist Alfred le Petit depicted a man knocking on a door while holding a giant playing card representing Bellot as king of hearts, holding a mug of beer. Manet was often accused, most famously by Gustave Courbet, of flattening his subjects and making paintings that resembled playing cards. (This invitation is a jocular reference to Manet’s original painting of Bellot ; both show the portly, bearded figure in similar format, close up and wielding a beer in the left hand, while the pipe that Bellot holds in Manet’s painting is transformed into a sceptre in le Petit’s variation.) Manet’s early biographer Adolphe Tabarant claimed that the artist painted La Palette au Bock in celebration of Le Bon Bock’s success, and that the palette was the same one that Manet had used for that canvas. Once embellished with the mug, the palette was shown in a fashionable boutique of curiosities on rue Vivienne where it functioned as a sign of Manet’s practice just as the tavern signs depicting beer mugs that frequently featured on the invitations to the Dîners du Bon Bock were a summons for the crowds united in celebration of liberal artistic ideals. Frédérique Desbuissons has argued that the painting Le Bon Bock was itself a sign, painted after the Franco-Prussian War, for the values in art and politics that Manet and colleagues had espoused in brasseries such as the Café Guerbois under the Second Empire, and around which they would rally in the 1870s. Manet’s critics were also fond of comparing his paintings to signage, implying that they were unrefined. Ernest Duvergier de Hauranne wrote in his review that “there are certainly tavern signs that are more life-like” than Manet’s submissions to the 1873 Salon, Le Bon Bock among them, and a Latin Quarter brasserie actually took a reproduction of Le Bon Bock as a sign.

Édouard Manet, La Palette au Bock, oil on palette, 1873. Courtesy of the Wildenstein Institute Archives, Paris.

Allison Deutsch

“Good Taste: Metaphor and Materiality in Nineteenth-Century Art Criticism”, Objet: Graduate Research and Reviews in the History of Art and Visual Culture, No. 17, 2015

(Passage quoted in extenso)